Fractures and exostoses of the splint bone

They’re small but they play an important support role in your horse’s leg. DR LAUREN JORDAN discusses splint bone injuries and their treatment.

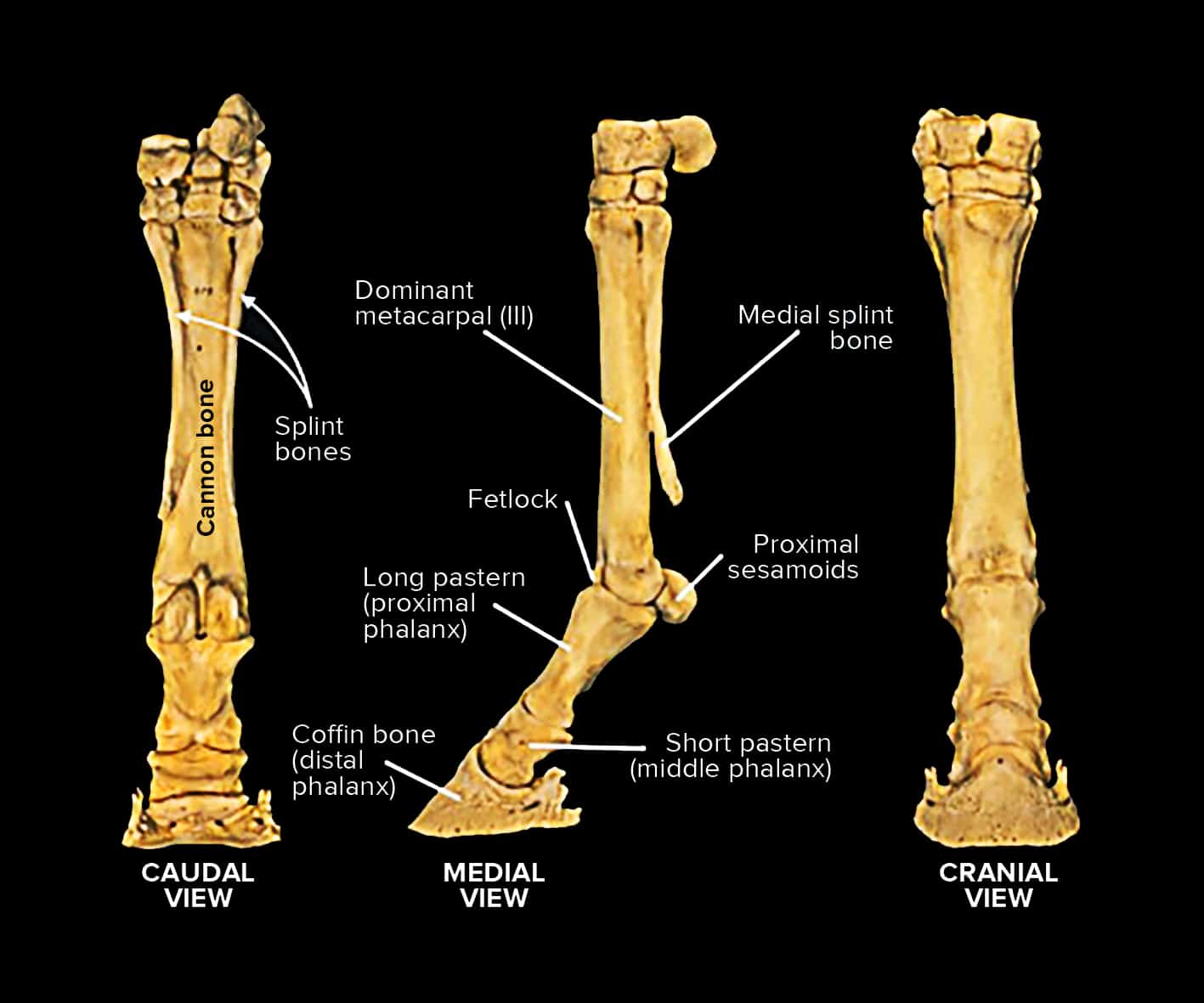

Have you ever heard your vet say that your horse has ‘popped a splint’ or that they have a splint fracture and thought what on earth does that mean? The splint bones are small vestigial bones that run along the inside and outside of the cannon bone in each leg. Whilst comparatively small, they are important bones in the support structure of the horse’s carpus (knee) and hocks.

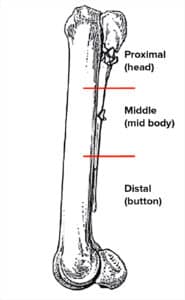

Lengthways from top to bottom, the splint bones can be divided into three regions: proximal – the head; middle – the mid body; or distal – the button (see Fig.1). The two main types of injuries we see with these bones are from traumatic injuries, causing a fracture or an exostoses (generally known as a splint).

Fractures of the splint bone can occur anywhere along the length of the bone and are most common in the lateral splint bones (which are on the outside of the limb), as these are the areas more exposed to kicks and other traumas. In contrast, exostoses or splints tend to occur more often in the medial splint bone (especially in the front limb) and can be related to poor conformation, working on hard surfaces or trauma.

Splint bone exostoses

Exostoses can be acute or insidious in onset depending on their cause. The condition is an inflammatory reaction in the bone and periosteum (the membrane covering the outer surface of the bone), resulting in a firm, painful swelling over the affected splint bone and surrounding area, which is usually sore to palpate. Mild to moderate lameness is usually present in the acute phase and is worse when the horse moves on a circle or is on a hard surface.

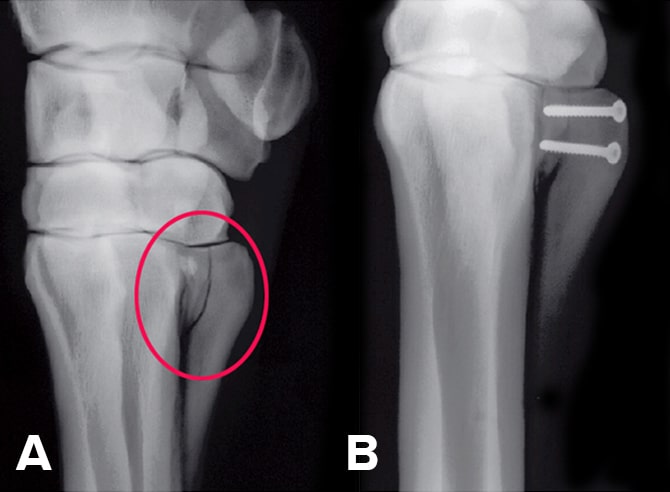

The mainstay of treatment of exostoses in the early stage is rest and anti-inflammatories. Ice, phenylbutazone and topical DMSO are used. The horse should often be confined to a smaller area for a period of two to six weeks until there is an improvement in the lameness. When examining splint bone exostoses, radiographs are indicated (Fig.2 A) and careful palpation of the tendons and ligaments is important as there can be impingement on the suspensory ligament when the exostoses occurs closer to midline. Sometimes an ultrasound is recommended to check the suspensory ligament especially with larger exostoses. Most horses respond well to this treatment plan and the lameness resolves. However, the bony protrusion does not resolve but may flatten out over time and will become nonpainful.

In some rare cases surgery may be indicated if the exostosis is particularly large and towards the back of the limb, or if it is impinging on the suspensory ligament, or if there are recurring flareups. Surgery can be performed to remove the affected splint bone or a portion of it, but it is important to let the acute inflammatory phase resolve completely before considering surgery. However, there is the possibility of regrowth following surgery, especially if factors such as the horse’s conformation were the initial cause of the problem.

Splint bone fracture

Depending on their location, splint bone fractures can be divided into those that are proximal, closest to the middle; the middle; and distal, the furthest from the middle (Fig.2 B). Their management depends on the location and also which splint bone – inside or outside, front or back leg – is affected.

The mainstay of therapy in the acute phase is stall confinement, anti-inflammatories, bandaging support, and perhaps antibiotics if there is an open wound. Radiographic and possibly ultrasound assessment is warranted to guide the most appropriate treatment plan, which can be highly variable based on the above factors.

Distal fractures occur at the bottom end of the splint bone and can be secondary to either internal (suspensory ligament desmitis) or external trauma. If the fracture is minimally displaced it can be treated with rest. However, as this end of the splint bone is fairly mobile, surgical removal of the fragment usually results in a better outcome.

Fractures of the middle part of the splint bone are a common traumatic injury and can involve multiple fracture lines. If the fracture is fairly simple with minimal displacement, treatment with rest and anti-inflammatories is typically recommended. If the fracture is associated with an open wound, the area will need to be flushed and debrided and the horse treated with antibiotics. Sometimes these fractures can heal with excessive callus formation, or smaller pieces of bone can go on to become sequestered (a small piece of dead or infected bone that forms a draining tract). Typically for these cases, conservative management is recommended in the initial period, but surgery to remove a portion or lower half of the splint bone may be needed in the weeks or months ahead (Fig.2 C).

Depending on which splint bone is affected determines how much of the bone can be safely removed, as the medial (inside of the leg) splint bones have a much greater role in support of the upper joints – the knee and the hock – and in weight bearing, so no more than two-thirds of their length can be removed. The lateral hind splint bone is the only one that can be removed in its entirety if needed.

Fractures of the proximal splint bones are more serious as they are more challenging to treat and can develop complications involving the knee and hock joints. When the fracture is open and involves multiple pieces, they are best managed conservatively with standing flush, debridement and antibiotics. There are some fractures that may require surgery, however, in this location the fracture fragments usually need to be stabilised with internal fixation which comes with a higher risk of infection and postoperative complications (Fig.3 A & B).

In summary, while the splint bones are small structures, they have an important role in the biomechanics of the horse’s limb, and the treatment of splint bone problems are highly variable based on their location and specificity of the injury. A thorough assessment is always recommended to ensure the most appropriate treatment plan is made for your horse.

Lauren Jordan BVSc (Hons) MS DACVS-LA, is a vet at the Apiam Agnes Banks Equine Clinic.