Social licence and the Five Domain Model

Following on from last month’s feature, we spoke to DR ANDREW McLEAN on the topic of social licence and the Five Domain animal welfare model.

Dr Andrew McLean is the CEO of Equitation Science International, an Honorary Fellow and Trustee of the International Society for Equitation Science, Director of the Racing Victoria Equine Welfare Advisory Board, Director of the Human Elephant Learning Programs Foundation, a Patron of Pony Club Australia, and in 2020 he was instrumental in reshaping the Five Domains welfare model.

An expert in his field, we invited Andrew to discuss both social licence and its relevance to horse sports, and the Five Domain model for animal welfare assessment.

Dr Andrew McLean:

Because of the increased public interest in how we manage horses, and some of the things that have happened in horse sports and in racing, I have no doubt that we need to be very concerned about the social licence to operate horse sports

The issue of social licence is one that is continuing to grow: all equestrian codes and all animal industries are subject to the same community expectations of good and appropriate animal welfare, and to community reassessment of animal management practices. As equestrians, it’s no longer good enough to say that that’s what we’ve always done, or this is tradition, or even that we, as people who work with horses, know what we’re doing while those that don’t do not. Now it’s really all about perception: what the public sees in the media and through camera lenses that capture everything that happens in fine detail.

I think it’s the end of the ‘behind closed doors’ mentality in all aspects of animal training and welfare. And that’s thought-provoking for me because of my interest in elephants. For example, it’s now rare to be offered elephant riding in Thailand because of a BBC documentary showing how they were trained (which was pretty brutal) behind the scenes – but in saying that, when elephant trainers see what happens in horse training, they too can be quite shocked!

Now that riding elephants has become vilified, you’re more likely to be offered other experiences with them, which ironically are not necessarily beneficial for the elephant. There are good arguments that at least when elephants were ridden, they had social contact and could explore and forage. Now they are chained and for the purpose of tourist entertainment are maybe walked 20 meters to do a painting or something equally absurd before they’re taken back to their lonely stall.

So, it’s not always a positive thing when animal rights drive change, and I believe this is why we have to be proactive in the horse world and to think about the future, how we can maintain our horse sports, and be prepared to move on and try new things.

To do this, our own perceptions of what is ‘normal’ need to change. Spurs are a good illustration of this: in my foray into the world of dressage it was compulsory to wear spurs, and I just took it for granted that that’s what you did. And then a friend, who didn’t know anything about horses or horse sports, came with me to a dressage competition and asked what the steel pieces on riders’ boots were. When I told him they were spurs and explained what they were used for, he was horrified – and it made me realise how much of what we do becomes normalised.

New normals

New normals are being established all the time, sometimes for better or, in the following example, for worse. Other than double bridles with cavesson nosebands, hardly anyone used nosebands in the ‘60s. Then that changed (possibly with the advent of Röllkur, which could be achieved more effectively with the use of a tight noseband) and suddenly tight nosebands had become standard practice.

So, to be sustainable, what must happen in horse sports, which I love, is for us to create and embrace new, best practice normals. Eventing has been very good in that respect. The old, extreme, long format three-day event has changed considerably because of the public outcry regarding horse welfare. Now policies have been implemented to make it safer. And all horse sports need to be moving in that direction. I think disciplines such as dressage and perhaps show jumping have in some respects defended what they do rather than rethinking their sport.

Positive changes

In order to maintain our social license to operate, I think there are a number of positive changes we could make. One is to demonstrate self-carriage, in other words that the horse has been trained to do something without any further nagging from the legs or being held in a frame. If we can show, by loosening the reins or by taking off our legs for a couple of strides, that self-carriage is maintained, then we’re proving that in a sense, the horse is choosing to do it, and that their mental security and wellbeing are therefore much better guaranteed.

Another change is to rethink the gear we’re using. Perhaps we should be rewarding our horses in training, rather than using all manner of coercive gear, while at the same time trying to justify that gear as if it isn’t coercive.

Some animal rights activists are promoting the idea that it’s wrong to ride horses. I don’t agree, they’ve been with us and ridden for probably over 5,000 years, and I believe there is such a thing as a species right to exist. In many ways I think horses may even get some enjoyment out of going places and doing different things, rather than living an empty life in a paddock. But if we don’t listen to mounting public sentiment, horse training may go the way of greyhound racing, where suddenly it could be severely curtailed.

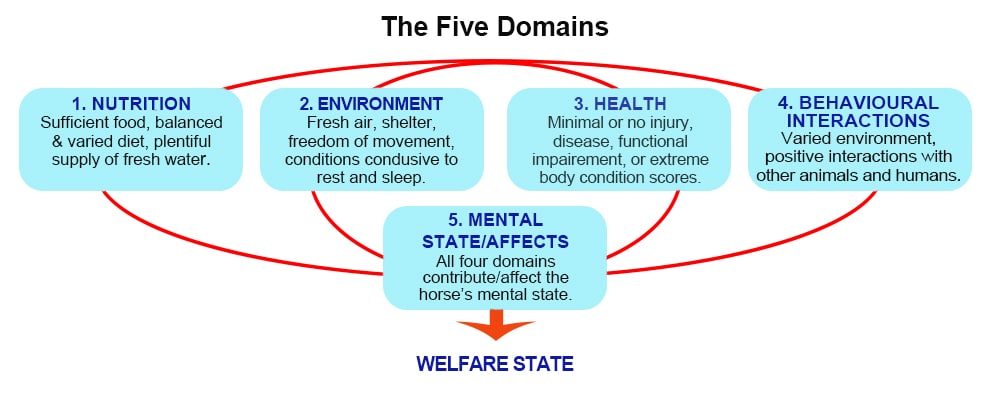

When we’re training or interacting with our horses, we must do it from their perspective and with their welfare front of mind – and the Five Domains model is an excellent tool for assessing and monitoring our horses’ welfare. Revised in 2020, the Five Domains are:

- Nutrition

- Environment

- Health

- Behavioural Interactions

- Mental State

The fourth domain was previously known as ‘Behaviour’, but the name was changed to reflect sentient animals’ innate capability to consciously interact with their environment, and with other animals and humans.

A life worth living

Developed around 25 years ago, the Five Domains model is about looking at animals not as objects, but as subjects capable of having positive as well as negative experiences. Interestingly, the Five Domains are inherently about us realising that we should do our best to give animals more positive mental affective states, in other words lives worth living. Therefore, the fifth domain, the mental state, should be the outcome of a horse receiving adequate nutrition in a physical environment conducive to their wellbeing, appropriate veterinary care, and optimal interactions with humans and other animals.

This is a very interesting shift, which I think tells us a lot about the evolution of our own consciousness, and reappraising what we do. For instance. The first domain is related to nutrition, but it is also about foraging behaviour. It’s important for horses to munch on hay for as many as 13 hours a day (you can always offer the hay in a slow feeder if you’re concerned about your horse gaining too much weight) not just for nutrition, but also for their mental state. We know if we deprive them of that, it can trigger oral behaviours such as wood chewing and wind sucking, and if they’re deprived of movement, they may weave or box walk.

These are markers of welfare that tell us what we’re doing wrong from the horse’s perspective. Similarly, although we accept and understand that humans are social beings for whom isolation can be devastating, we isolate horses, who also thrive on social interaction. In the past few years I’ve been promoting taking down bars in stables so horses can access each other if they want to touch, because seeing is definitely not enough; being able to touch is vital for social animals.

No doubt this important article has given you plenty to think about. Head to Pub Med for a full explanation of the Five Domain Model, as well as some helpful diagrams.

Equitation Science International offers a Diploma of Equitation Science, a horse training and coaching qualification that provides a full understanding of horse training and enables the most effective pathways to all equestrian disciplines and activities.