Poultices are uniformly moist and soft; can be icy cold through to quite warm, and are usually based on clay, writes DR JENNIFER STEWART.

Poultices can include cereals, plant materials, astringents, emollients and antibiotics; they can be commercial or home-made; and their exact action changes with the temperature, application method and ingredients.

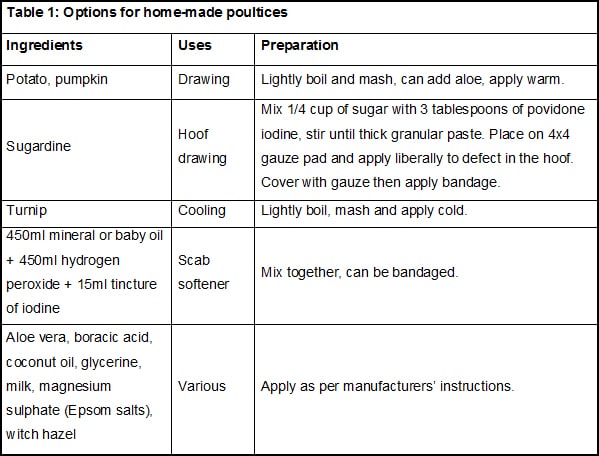

Before using any poultice check the ingredients. Although mud alone can act as a poultice, there are cleaner and more effective options (see Table 1).

Cold therapy: Generally, cold poultices are best for acute injuries, bites, stings and after exercise. Used to reduce pain, minimise swelling and decrease inflammation, they are a form of ‘cold therapy’. Although cold hosing and ice are more effective for cooling the legs, a clay-based, cooling poultice is an alternative for reducing heat after work. As the clay dries, fluid is drawn from the underlying tissues, and as the water evaporates it takes the heat with it.

Similar to ‘icing’ an injured area, a poultice can provide hours of therapy. However, the heat from your horse’s leg will gradually warm the poultice and if it has been bandaged, the area may become even warmer. A damp cloth or moistened brown paper placed between the skin and the poultice will keep the poultice and the area moist and cool for longer.

Because cold therapy poultices help to reduce pain and minimise swelling, a practice across many disciplines is to use them on muscles, tendons, ligaments and joints both before and after exercise. When competing, horses work harder, travel further and are confined more so they experience greater musculoskeletal stress, which predisposes them to injury. Daily poultices help horses to recover and recuperate well.

Usually based on clay or salt the poultice material is cooled in the fridge and then spread thickly on the legs: the cannon bones, tendons and ligaments. Known as ‘setting-up’ or ‘sweat wrapping’, in this case more is better! After hard work the poultice is applied to all four legs and covered with a damp cloth or paper. The temporary cooling and natural astringent properties help minimise swelling, soreness, stiffness, inflammation and support faster recovery, as well as helping reduce fluid build-up in horses suffering from strains or other injuries – but it is totally unsuitable for open wounds.

Heating or cooling: After daily workouts, some horses do best with a short-term cool poultice, while others respond to a heat-inducing poultice. If there is localised swelling it can be cold-poulticed while waiting for your vet. A cooling poultice will also make your horse more comfortable after an insect bite or sting. Cover each welt completely with a thin layer of the poultice. There’s no need to bandage and by reducing the irritation of the bite there’s less likelihood they’ll rub on fences or stall walls.

Warming: Warm poultices help increase blood flow to the area – an important part of healing and great for older injuries and abscesses. Surface heat can penetrate about 2cm – decreasing blood pressure, superficial muscle spasm and pain, while increasing blood flow, cell metabolism, muscle relaxation and tissue elasticity.

Heating: When there is pain, joint stiffness and reduced range of motion, your vet may recommend heat therapy for 15-30 minutes, 2-3 times a day – usually starting within 24-72 hours after injury. Heat is contraindicated when there is acute inflammation, bleeding or fever, so act on your vet’s advice. And test the poultice on your skin first – it should be warm not hot.

Liniments: A useful first-aid kit inclusion, liniments are liquids or gels, with similar properties to poultices in that they are applied to the body to help with cooling, heating, pain, stiffness or soreness. Composed of plant extracts, essential oils and other compounds, they are usually based on vinegar, rubbing alcohol, aloe vera or witch hazel. The exact heating or cooling effect depends on the ingredients and how they’re applied. Massaging and rubbing-in can also be soothing and improve circulation. Due to their more liquid consistency, they are especially suited to the back and particularly useful for cooling after hard work.

Injuries & Laceration: Your vet may recommend a cool poultice for the first few days, before switching to warm poulticing. Alternating cool and warm poultices over a period of days works well for many horses. Common in many sports, over-reach wounds of the heel and stud-related punctures can be quite painful. With water jumps, these wounds are often contaminated, require antibiotic therapy and tetanus prophylaxis. Apply a drawing poultice while waiting for your vet.

Foot abscesses: Heating poultices help draw out pus and inflammation, and are useful for foot abscesses, bruising and sole injuries. Prolonged rain increases the incidence of foot abscesses, so check your horse’s feet. After periods of drought, hooves soak up water quickly and any wall cracks can become packed with mud and bacteria, which then gain entry to the sensitive structures of the hoof, and potentially the pedal bone. Within days an abscess can form – producing bounding digital pulses, heat along the coronary band, pain, swelling of the pastern and fetlock, and acute lameness. To help prevent abscesses, keep hooves clean and spray or paint the sole daily with a 50:50 mixture of methylated spirits and strong iodine.

Poulticing the hoof helps soften the sole and draws out pus. Use a warm poultice (Epsom salts or sugardine), apply and wrap/bandage in place. Change the poultice after eight hours. If the abscess doesn’t burst, your vet may apply an overnight poultice (often consisting of a five litre bag containing a porridge of bran, warm water, betadine solution, epsom salts and DMSO) to soften the hard epidermal tissues and encourage drainage. Once drainage begins, continue poulticing the foot for several days. If the discharge persists or abscesses recur, x-rays may be required to rule out pedal bone infection or osteomyelitis.

Hoof abscesses can be relatively simple and uncomplicated, or more serious than they initially appear. So if your horse suddenly becomes lame (either mild or three-legged) call your vet, and also ensure your horse’s tetanus vaccination is up to date.

Old injuries: May respond to a version of the setting-up system. You definitely want warmth on the area, and to prolong the heating effect of a liniment, you can wrap in cellophane before putting on your cotton wrap. Always ensure your liniment is safe to use in this way and won’t blister the leg.

Sole bruising: May occur acutely (e.g. stepped on a stone, concussion) resulting in lameness from the bruising which may or may not develop into an abscess. Either way, if your horse is lame in the foot, initiate treatment with a poultice to help draw out bruising – and an abscess if one forms – before your vet arrives. Because the pedal bone is so close to the sole, there is the ever-present risk of subsolar abscesses becoming osteomyelitis. Call your vet if poulticing isn’t reducing pain or the lameness is severe. Your vet may have to create a drainage tract to allow fluid and pus to seep away from the abscess. If that’s necessary, poulticing the foot is often part of the ongoing treatment process.

Wounds: Poultices can also be applied to wounds. ‘Wound’ is a broad term and includes anything from minor scratches to degloving injuries. But most significant is the anatomical location. An inconspicuous puncture wound or laceration over a joint or tendon sheath can be far more sinister than a shocking wound on a fleshy area. Don’t wait, call your vet – their early intervention can save you time, money and your horse’s wellbeing.

The final word

When your horse sustains a wound or injury there are many bandages, liniments, poultices, salves and treatments available, and this is definitely not the time to ask Dr Google for advice! To avoid harming your horse and potentially making matters worse, consult your vet. Nothing – including the information in this article – should replace their expert guidance.

Dr Jennifer Stewart BVSc BSc PhD is an Equine Veterinarian, CEO of Jenquine Equine Clinical Nutrition and a consultant nutritionist.