Jolanda Adelaar is a Grand Prix dressage rider, Vegan athlete and Equine Behavior therapist based in the Netherlands. Many people are familiar with her incredible work with Super Guus, Jai and Carletto. But not so much is known about Jolanda herself. JESS MORTON found out more about her special bond with Guus starting at age 12 and more about her journey as a professional dressage rider.

At what age did you become interested in riding?

I started riding at seven years of age at a local riding school. I do not come from an equestrian background, but in the Netherlands, equestrian sports are fairly accessible to most people in some way or another. Everyone has a friend or relation that rides, and equitation in all of its many forms is an important part of Dutch culture.

The highlight of every week for me was that one hour of riding. I travelled back and forth to the school on my bike, and when I wasn’t on a real horse, I would pretend my bike was a horse. I even named my bike after my favourite school horse.

When did you meet your first horse Guus?

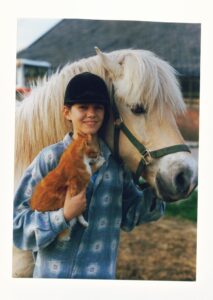

When I was twelve, my parents sent me to a summer camp where I would be able to ride every day for a week. It was there that I met a special Norwegian fjord horse who didn’t fit in with the riding school atmosphere. The connection was instant. That little horse was Guus.

It took me one year to convince my parents to buy him. We did not have the facilities for a horse at home, nor the experience of owning a horse. But I wouldn’t give up.

In the end, my father said to me he would consider buying Guus on one condition; I needed to find an affordable pasture to keep him. I took up the challenge and jumped on my bike on a mission.

I must have rung every doorbell in the area to ask if they had a pasture for rent, and in the end, my persistence paid off. I found a cattle farmer who agreed to let me put Guus in with his herd of cows for the equivalent of €30 a month. It was the happiest day of my childhood when my father agreed that Guus could come to live with us.

In the beginning, I had to ride bareback because I did not own a saddle. We had no school to train in, so I rode Guus amongst the cows in the field. Our first bridle was something I made myself. After a year of riding alone, I joined the local pony club and we began to take weekly lessons there.

How did you get interested in dressage?

One day I watched a freestyle test on television. The concept of a horse and human dancing together intrigued me. I wanted to experience that with Guus.

I watched and recorded every international dressage show aired on TV, and I watched those tapes over and over. My parents had an old book from 1937 called “Rijden en africhten”. It did not have pictures in it, but it explained how to train high-level dressage movements like the airs above ground. I studied that book rigorously.

But I was told that I needed a sport horse if I was going to train for dressage. “Fjord horses are not made for dressage,” the experts said. They even recommended that I sell Guus and buy a more suitable, flashier breed. But that never felt right to me. To me dressage is for the horse, and not the other way around.

I figured that since a judge is scoring the correctness of a horse and rider, then the breed should not be important. If one reads the FEI rules, there is nothing in there that talks about judges giving higher scores to horses with flashy movement or front legs that reach for the sky. Correct dressage is about finding balance and harmony. Every horse with a spine and four legs can benefit from dressage. No matter the breed or the budget of the rider. This is what is so incredibly beautiful about our sport. It can benefit all horses and all riders.

My father, who has always been my biggest supporter, backed me up 100% when I announced I wanted to ride dressage with a Norwegian fjord horse. He was not a horseman, but he was a violinist, and he often compared classical dressage to playing a musical instrument.

Within 2 years, I was a regional champion at the Dutch Z2 level (Advanced Level) with Guus. This was an unusual accomplishment in Holland, and it landed us in the local press because of it.

We were invited to perform a special act at the FEI World Cup dressage in 2006 at ‘S-Hertogenbosch. In a homemade white dress, we demonstrated to everyone that a draft horse can do piaffe and passage too. I still remember the incredible feeling of sharing the warm up arena with some of the world’s biggest dressage names, like Isabell Werth and Anky van Grunsven.

Guus became the first Fjord horse in the Netherlands to compete at the Subtop level, and locally he picked up the nickname “Super Guus”. He soon had his own fan club and a book “Guus” that was published in 2006.

He is still with me and soon he will be thirty. That means he has been with me for 27 wonderful years. Sadly, my father passed away this year.

Tell us about your journey to becoming a professional rider?

Because of my success with Guus, people started requesting lessons from me, so I certified as a professional instructor and horse trainer. I was accepted into the Dutch Equestrian Sport Masterclass, (reserved for riders with proven success in top-level dressage) where I qualified as an instructor. After that, I studied to be an Equine Behavior Therapist at the Tinley Academy- and that is where I teach today.

I am an active member of the International Society for Equitation Science, and I have many years of professional riding experience while working in Italy. I am now competing Grand Prix level dressage with my Italian Murgese stallion, Carletto.

What makes the horse such an inspirational subject to you?

What has always fascinated me about horses, is the fact that these enormous sentient beings accept us riding on their backs.

If I think back, thousands of years ago, horses were eaten by humans and hunted down by them. Somewhere along the line, they allowed one of their key predators to domesticate and ride them. Even after everything we did to them, they had faith in humanity. Thanks to horses, humankind has won battles, travelled faster and further afield than we could ever have imagined would be possible. They have helped us extend our mental capacity too: since a good equestrian has to be emphatic enough to understand another species.

What is your favourite memory involving horses?

When I first brought Guus home, I was so happy that I wanted to lift him up like a puppy. That feeling that he was all mine and nobody could take him away from me was magical. For a child, owning a horse is a huge responsibility, but also a blessing that many are not able to experience. It was the best feeling in the world.

You started your own horse. Can you walk us through your training process, psychologically and physically?

It’s easier to send you over to YouTube to watch a clip I made. There I explain how I train all of my horses (if you skip to 6.37 minutes, it is in English). Watch it here.

And here is another clip where I explain how I train my young horse from the ground. This video has English subtitles if you click “subtitles” on the bottom.

You are now based in Holland but lived in Italy for a long time. What was that transition like and did it affect your riding at all? What is the equestrian community in Italy like compared to Holland?

The main difference between the Netherlands and Italy is that equestrian sport in Italy is less accessible for newcomers or competition riders. In Italy, horses are an elite hobby and everything to do with their care is much more expensive than it is in the Netherlands.

Italy is seven times bigger than the Netherlands, so for national competitions, you need to travel much further afield and often. In a regular dressage competition in Italy, your horse usually has to stay overnight at the venue. That means you have to book a hotel unless you have a lorry to sleep in. A dressage competition less than three hours away is considered close in Italy.

Here in Holland, every weekend there are a myriad of competitions to choose from, and none have travel distances over 30 minutes. You can pull up with your trailer, ride your test and then load up and head home again after. In the Netherlands, you pay around fifteen Euros to ride a test no matter which level you are competing at, and your show license costs around €120 a year. I paid €60 for every test in Italy, and my competition license cost me almost double what I paid in the Netherlands.

In Italy, there is also a ton of bureaucracy to deal with if you want to compete. Before you can ride in a show, you need to buy all kinds of mandatory stamps, collect signatures and file different papers. You have to contact each of the authorities and often need to go to each office in person to get paperwork signed, because they won’t accept online submissions. Everything to do with horses is complicated, including travel…

Every time you take your horse on the public road, you have to fill in a transport form and have it handy. One time I did not fill in this form properly, and I was stopped by the police on an Italian highway and kept on the side of the road for two hours with my horse inside the trailer. The police wanted to fine me €2000. I fought that charge, but I still had to pay a different fine of €600 for not writing the hour of departure on the transport form.

Where do you train? What is your daily schedule like?

At the moment, I train my horses on my own, and every day is different. Some days I am busy giving lessons at a clinic (thankfully, this is still possible during the pandemic).

Before Covid came along, I competed almost every weekend or performed in equestrian shows at events around the Netherlands. Sadly, events are not allowed anymore, and many shows have been cancelled since the start of 2020.

I teach at the Tinley academy science-based education on animal behaviour, recently mostly through Zoom due to Covid restrictions. I also work as an influencer on YouTube and Instagram, which requires that I edit videos/ create content. Outside of all that, I love to paint and make creative art.

How would you describe your style of training and riding? Would you characterize it as a specific genre?

Because of my background as a behavioural scientist, I am very conscious of how I use my aids and how my horse learns. I train consciously according to the learning principles of behavioural science, using classical aids from the saddle and positive reinforcement. This is a scientific term for adding a primary positive reinforcer to motivate behaviour. A primary positive reinforcer is naturally present in the horse’s world, and not conditioned externally. Giving your horse a pat on the neck is not a primary positive reinforcer. Examples of primary positive reinforcers are food and sex.

I use food rewards to train my horses with positive reinforcement from the ground and in the saddle. When you train with positive reinforcement, it is important to use secondary positive reinforcement as a bridge between the primary positive reinforcer. An example of a secondary positive reinforcer is a clicker. This is a small tool that makes a click sound but you can also make it with your tongue. When the clicker is conditioned for the horse, the horse knows that after the click sound comes food. When he hears the click sound, it activates a happy feeling in his brain. The behaviour that takes place at the exact moment of the click sound is the behaviour that gets reinforced. It allows me to be very precise in what I want to teach to my horses.

What do you aspire to as a rider and trainer?

I love to train horses up to Grand Prix level, and I discovered this is something I am also good at no matter the breed. I get a kick out of seeing horses transform through training. This is addictive. Especially when you can give an underdog a second chance to become valued. A horse that nobody cares for suddenly becomes visible, balanced, flexible, powerful and beautiful.

Can you tell us about what made you choose your horses breeds and how you found them to work with?

I choose my horses because of their characters. The inside is what counts the most for me. I know quickly if I have chemistry with a horse. I am HSP (a highly sensitive person), and this also helps when I am working with horses. A horse is not a car. They are sentient beings, just like us. With some horses I have an instant connection and with others less. Guus for example is not typical of his breeding. He is unique for a fjord, and can be just as fiery as a hot-blooded Arabian.

Regarding Carletto, because my mother is Italian, breeds from Italy were of particular interest to me. Italian horses have so much history behind them. When I visited Puglia to look at purchasing a Murgese horse, I selected Carletto because of the feeling he gave me. He was not saddle trained when I went to look at him, and I only saw him moving on the lunge. I groomed him and scratched his withers to evaluate how he responded. He carefully groomed me back. It was what I was looking for.

Favourite achievements with your horses?

My journey with Carletto is something I am very grateful for. I trained him to saddle myself and schooled him from the ground up to where he is today. He is the first Murgese horse in the world to compete at a Grand Prix level. The Murgese is an old Italian breed that has been bred for agricultural work. Just like with Guus, I was told at the beginning of my journey with Carletto that Murgese horses were not built to be sporthorses. I proved them wrong again. But it wasn’t through luck. I worked very hard to get Carletto to this level. Behind our successes were many years of blood, sweat and tears. Especially from my side!!!

Carletto is the sort of horse that does not like to waste his energy….But through positive reinforcement, using food rewards, I found a way to motivate him so he could reach the highest level of dressage. Here’s a clip of his story from 2021.

Do you have any advice for aspiring riders?

Be true to yourself. Know who you are and don’t let other people tell you who you are. Always stay humble and equally so, stay realistic. Nobody ever stops learning. But don’t let other people make you believe you are less worthy than them because of your background or because of the horse you ride.

I have successfully used visualization to get where I want to go. I believe this really helps to shape a dream into reality. Progress always starts from within.

What’s next for Jolanda and her trio of horses?

Guus is enjoying his retirement these days. He lives out and is great support for my young horse, Jai. My plans this year were to compete for Italy internationally in the Grand Prix with Carletto. But because of the pandemic, my aspirations feel very far away at this moment. The Netherlands is again in full lockdown, and competing internationally costs a lot of money. Riding in venues without an audience, or travelling with the constant risk of events getting cancelled is not very appealing to me right now. I want to give everything I have to be selected for the big events. I want to give my whole heart to this journey and not live in fear. We are not living in the old world anymore, and trying to get that world back only causes more frustration.

What I can do now is try to make the best of what I have got, and focus on things I have control over. I am blessed to have many people requesting lessons from me through Zoom and Pivo.

Before the crisis, I focused on real life lessons and clinics. Today I am exploring the virtual possibilities of teaching horses and riders in different time-zones all over the world.

Final Worlds As We Say Goodbye to 2021

I strongly believe the world is going to be a better place once we come out of this crisis and the whole story is seen by everyone.

My father was my biggest supporter, and his death earlier this year had an immense impact on me. When I hear people on TV talking about Covid, they never mention the number of people who died because of the governmental restrictions and cancelled treatments. Those numbers are just as serious. My father died only two weeks after he got diagnosed with asbestos cancer. Like him, there are so many people around the world that have died because they could not receive life-saving medical treatments. Many people had to die alone in hospitals because visitors and loved ones were not allowed. Even hugging at funerals was not allowed. Mental illness is rampant because of the enormous emotional impact we are all feeling because of isolation, loss, and fear. But I have faith in the future. If we build it on truth, then the future can only be good. But for now, I have to make the best of what is possible and right.