Diseases of domestication

Horses have been domesticated for thousands of years, but this has not always been to their advantage, writes DR JENNIFER STEWART.

Domestication is ‘… to adapt by selective breeding an animal or plant from a wild or natural state to life in close association with and to the benefit of humans.’ Long before domestication, lies 60 million years of horse and 6 million years of human evolution. No clear centre of domestication has been identified for the horse, instead it appears that there were multiple sites across the plains of Eurasia around 5,000 to 6,000 years ago.

At 5,500 years ago, the Botai culture of Northern Kazakhstan is thought to be the earliest, with evidence of harnessing, milking and corralling, followed by other centres in Iberia, Eastern Anatolia, Western Iran, Levant and Hungary. However, substantial changes in the ancestry, physical form and structure that differentiate wild and modern domesticated horses only appear 3,000 years ago in the early Iron Age. Coat colouration was one of the earliest traits and around 2,500 years ago, horse breeders from Central Asia targeted genes selecting sturdier limb formation and quieter temperament, while around 1,000 years ago, speeds and gaits were the focus. Early breeders maintained diverse genetic resources from multiple stallions and an endless supply of mares, but in the last 250 years, overall genetic diversity has dropped by 16 per cent.

Domestication is generally associated with certain genetic costs, including overall fitness. Smaller population sizes during domestication and targeted artificial selection for breed-defining traits has, compared with their wild ancestors, unintentionally increased the number of harmful genetic variants and mutations. This is one of the so-called ‘costs of domestication’.

Horses have been selectively bred for performance traits such as speed, endurance, strength, gait, appearance and temperament, resulting in 400 to 500 different breeds and over 130 hereditary diseases. Inbreeding and low genetic diversity, particularly over the last 200 to 400 years has resulted in some breeds having increased susceptibility to hereditary diseases and reduced fertility rates.

A free-living lifestyle

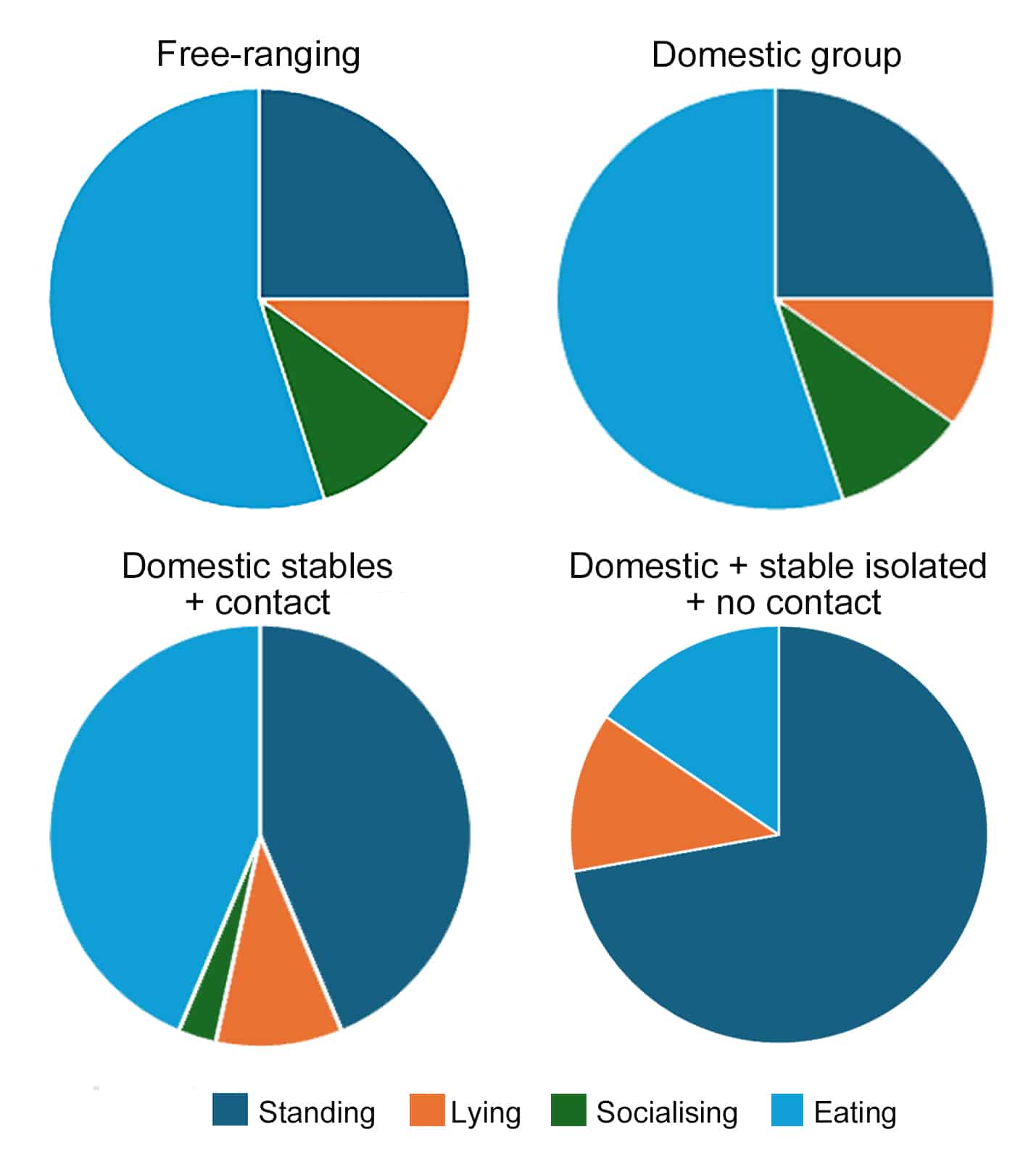

Free-ranging and feral horses live in large, stable groups with the most dominant mare at the top and a circular hierarchy below. They roam over up to 48 square kilometres, spending 12 to 18 hours each day foraging on roughage, mostly grass. Variable nutritional values of grass required the digestive system to evolve for continuous grazing and a high throughput. To match this, there is continuous gut motility, continuous secretion of stomach acid, and no gall bladder. The role of the gall bladder is to store bile between meals and because horses don’t naturally eat meals, there was no need for a gall bladder! The rest of the daily time budget in the free-living lifestyle typically involves 2.5 hours lying down, 5 hours standing and 2.5 hours grooming and socialising (see Figure 1).

Due to seasonal changes, feral and free-ranging horses gain weight during summer when food is abundant, losing it again during the winter when food is scarce. Even today, feral and free-ranging horses and ponies retain strong seasonality with respect to appetite and body condition, and an annual cycle of gaining and losing weight without negative health effects. Domestication hasn’t changed these natural, instinctive behaviours and in this, our horses are not far removed from their ancestors. In fact, horses who escape captivity readily re-establish similar behaviours to their free-ranging counterparts – indicating that horse behaviour is largely unchanged despite domestication.

The process of domestication introduced new challenges for the horse, including restricted movement, changes in diet, and reduced social interaction. Some of the changes introduced with domestication conflict with the horse’s natural lifestyle and can result in abnormal behaviours and increased health problems.

The modern lifestyle

Confinement and abundant food parallel the modern human lifestyle responsible for endemic levels of obesity, cardiovascular disease, arthritis and diabetes. Domestic horses have become more sedentary since the industrial revolution. For horses, diseases of domestication associated with restricted movement and modern diets include stereotypies, colic, stomach ulcers, equine metabolic syndrome/insulin dysregulation/laminitis and developmental orthopaedic diseases:

Stereotypies: Stereotypies in domesticated but not free-range or feral horses, are coping mechanisms that result from a man-made environment. Found in 15 to 38% of domestic horses, they are compulsive behaviours that occur when they are faced with insoluble conflicts. Environments are particularly stressful if they inhibit the expression of instinctive behaviours. Compulsions reflect aspects of natural movement, feeding and sexual behaviours. Compulsive stereotypies related to movement include stall walking, weaving and pawing. Domestic horses are often unable to move around freely over large areas and those kept in small yards or paddocks travel around 1km/day compared to pastured horses travelling 7.2 km/day – still much less than their ancestral or their free-ranging counterparts.

Stereotypies linked to diet and feeding management include cribbing, wind-sucking, weaving and circling. Other factors contributing to weaving include decreased social contact, restricted exercise, concentrate feeds, limited roughage availability and anticipation of meals. Stereotypies related to an unnatural diet may include lip flapping, wood chewing, cribbing, tonguing, and aerophagia. Crib-biting, which reflects adverse early life experiences, specifically weaning, occurs in around 19.5% of endurance and 32.5% of dressage horses. Feral horses dig, chew wood, and eat earth as part of natural behaviour, but compulsive behaviours do not occur. Masturbation and flank biting (also known as self-mutilation) are related to inhibition of natural sexual behaviour. Overt aggression is rare in feral and wild horse herds once the social hierarchy is established and aggression in domestic horses is related to reduced opportunities to socialise.

Colic: Limited physical activity can reduce or change the sequence of intestinal contractions, increasing the risk of colic. Meal feeding and lack of exercise (Figure 1) change the water balance in the gut and contribute to intestinal inflammation, diarrhoea and diseases as severe as colitis, large colon volvulus and torsion. Colic is more common in crib-biting, wind-sucking or weaving horses – all associated with low-fibre diets and high concentrate intake. Another risk factor is changes in the biome, which differs between feral and domesticated animals. Horses fed a concentrate diet versus a grass-only diet have an increase in lactic acid-producing microbiota, which is found in horses that develop colonic distension or impaction. In semi-feral and free-ranging horses, the intestinal microbial richness, abundance and diversity are high due to the variety of plant species in the diet. Domesticated horses adapted to diets higher in sugar and starch have a lower microbial species diversity and richness. There are also differences in microbial composition in horses with chronic laminitis, and those with EMS.

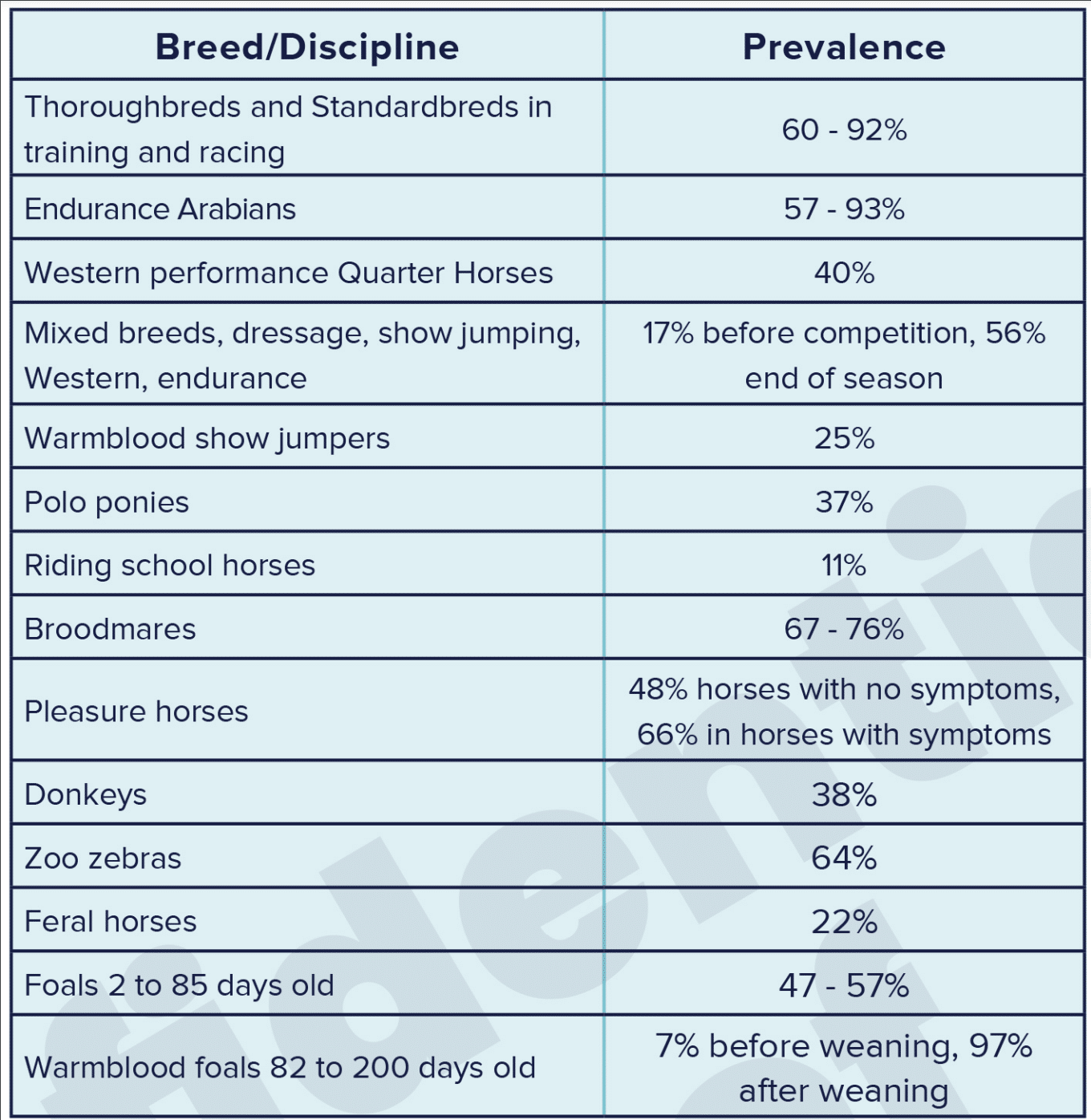

Ulcers: Given that stomach ulcers are also encountered in feral horses, they are likely to have been around for as long as horses – suggesting that some degree of ulceration is natural. However, the prevalence, severity and incidence is much higher in domestic horses (Table 1), the signs more intense, and healing slower. Interestingly, other factors affecting the incidence, location and severity of gastrointestinal ulcers include the trainer, high starch/low roughage diets, fasting, confinement, transport, and limited access to water. In free-ranging and feral herds many horses don’t show signs and mild ulcers can heal spontaneously.

Another aspect of natural feeding behaviour is the position of the head. Natural grazing occurs at ground level and any higher position during feeding contributes to dental problems. In addition, widespread dental pathologies found in domestic but not free-roaming horses include wear on the lower second premolar, and bone spurs between teeth caused by the bit, which can result in trauma to the jawbone and much faster erosion of the rigid enamel plates.

EMS, insulin dysregulation & laminitis: Laminitis occurs in wild-living horses if their carbohydrate intake is high during seasonal abundance of grass. Studies on free-living herds in Australia, New Zealand, Japan and Europe have all found that although most animals had no visible signs of laminitis, up to 80% of horses had hoof rings characteristic of laminitic episodes. The natural seasonal weight loss and gain typical of feral horses may serve as a counterbalance to periods of increased nonstructural carbohydrate-rich food consumption.

Many domesticated horses experience chronic over-nutrition and the seasonal changes in body condition and insulin sensitivity are replaced by progressive obesity and insulin dysregulation, predisposing them to laminitis. The heritability for traits associated with equine metabolic syndrome (EMS) is quite high and linked to genetics – all breeds that have a higher risk share two major genes responsible for elevated blood insulin and triglyceride levels.

Hooves and feet: The concepts of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ foot in domestic horses refers to horses living their entire life without any hoof problems as opposed to those with chronic hoof maladies from a young age. However, a genetic survey found no marked difference in the breed origins. In feral horses, small hoof cracks seem to be a natural occurrence in self-maintaining hooves and are influenced by ground hardness and seasonal environmental changes. Soft substrate and wet periods with lush forage appear to induce growth, while hard substrate and dry weather induce self-trimming with the appearance of cracks. Large cracks running from the sole to the coronary band of the hoof are uncommon in wild-living horses because in most wild-living conditions they are able to move sufficient distances on diverse surfaces to wear their hooves down.

With podotrochlosis (navicular disease), nature and nurture are both implicated. In some horses there is an inherited risk while in others, management, conformation and work predispose to the disease. Genetics is the most common risk factor. With their small feet, Quarter Horses have the highest occurrence, followed by Warmbloods and Thoroughbreds. Foot conformation has a big impact on the amount of strain the navicular apparatus endures and concussion causes tissue damage. Many horses with caudal heel pain have a low heel and long toe which forces the pulley system in the foot to work harder to lift the foot off the ground. In horses with such conformation, the navicular apparatus isn’t being used as designed, resulting in abnormal concussion on the bone and soft tissue structures.

DOD: Another disease widely recognised as man-made is developmental orthopaedic disease (DOD). In feral horse populations it is very rare (around 2-5%); in domestic horses it affects 10-65%. The incidence is highest in Warmbloods, Thoroughbreds and Quarter Horses, and is linked to rapid growth and biomechanical factors. Contributing influences include nutrition, exercise, conformation, trauma, stress, maternal nutrition, and hormonal interactions. Genetics is also heavily involved contributing 40% of the risk, with 60% environmental/man-made. New genetics research shows that environmental influences can actually affect whether and how genes are expressed. In fact, scientists have discovered that early experiences can determine how genes are turned on and off and even whether some are expressed at all. The old ideas that genes are ‘set in stone’ or that they alone determine development have been disproven. Altered gene expression has been found in DOD lesions in young horses fed a high energy diet for several weeks.

The pros and cons

Health problems that may be encountered in wild-living horses are difficult to assess. But in case we let ourselves be carried away with the magic of the wild horse’s life of liberty and freedom, it’s worth remembering that free-living horses are subject to perils that make survival precarious. Predators, high levels of parasitism, harsh weather and insects, scarce resources, and fights between stallions all endanger free-roaming horses. Without human protection, they can suffer hunger, thirst and health problems. However, wild-living horses still have a considerably healthier lifestyle compared to their domestic counterparts and the question of whether diseases of domestication are due to nature of nurture is no longer a debate – it’s nearly always both!

Dr Jennifer Stewart BVSc BSc PhD is an equine veterinarian, a member of the Australian Veterinary Association and Equine Veterinarians Australia, CEO of Jenquine and a consultant nutritionist in Equine Clinical Nutrition.

All content provided in this article is for general use and information only and does not constitute advice or a veterinary opinion. It is not intended as specific medical advice or opinion and should not be relied on in place of consultation with your equine veterinarian.