Dealing with anthelmintic resistance

The resistance of parasites such as intestinal worms to anthelmintic de-wormers or drenches shouldn’t be taken lightly, as DR SARAH GOUGH explains.

The introduction of modern day anthelmintics heralded the steady decline in some parasite associated diseases, some of which were severe. Earlier treatment recommendations were aimed at parasite eradication, which led to a considerable reduction in some target parasite species, but unfortunately, frequent anthelmintic use also led to the development of resistance in other species.

Antimicrobial resistance is a health concern many people are aware of, but less well known is the problem of anthelmintic resistance, the resistance of parasites such as intestinal worms to the active ingredients in anthelmintic de-wormers or drenches. The impact of anthelmintic resistance is more covert as we can’t readily see the worms within the gastrointestinal tract, and the disease caused by them is slow and insidious in many instances. It poses a big threat to our equine companions, as well as other domestic and farm species. As such, parasite management plans, and associated recommendations for horse owners, have changed considerably in the last few years.

Susceptibility and resistance

Anthelmintic resistance is the term used to describe the ability of the parasite to withstand or survive in the face of a treatment with a specific anthelmintic. Some parasites have an inherent resistance, that is they have never been susceptible to that class of anthelmintic, while others are developing resistance genes similar to the way that bacteria develop resistance genes to antimicrobials. The development of resistance genes in parasites is, to some degree, inevitable. However, the overuse of anthelmintics leads to increased exposure and hence an increased rate of resistance development. Conversely, a more prudent and targeted use of anthelmintics slows the rate of resistance development.

Parasites of concern

There are many different parasites that affect horses, and depending on the horse’s age, some may be more important than others. Ascarids such as Parascaris equorum can cause disease in young horses up to one year old, after which they are rarely associated with disease. Small strongyles cause disease in horses of any age and are the primary parasite of concern in adult horses. Tapeworms can also cause disease in horses of all ages, although this is not common.

Parasite management plans are typically designed to control strongyles and tapeworms (and ascarids in young horses) and these programs, if executed well, also manage other parasites such as Habronema, bots and pinworms, while taking into account individual factors such as immune status, concurrent health conditions and so on, all of which may influence your horse’s ability to manage their parasite load.

Intestinal worm lifecycle

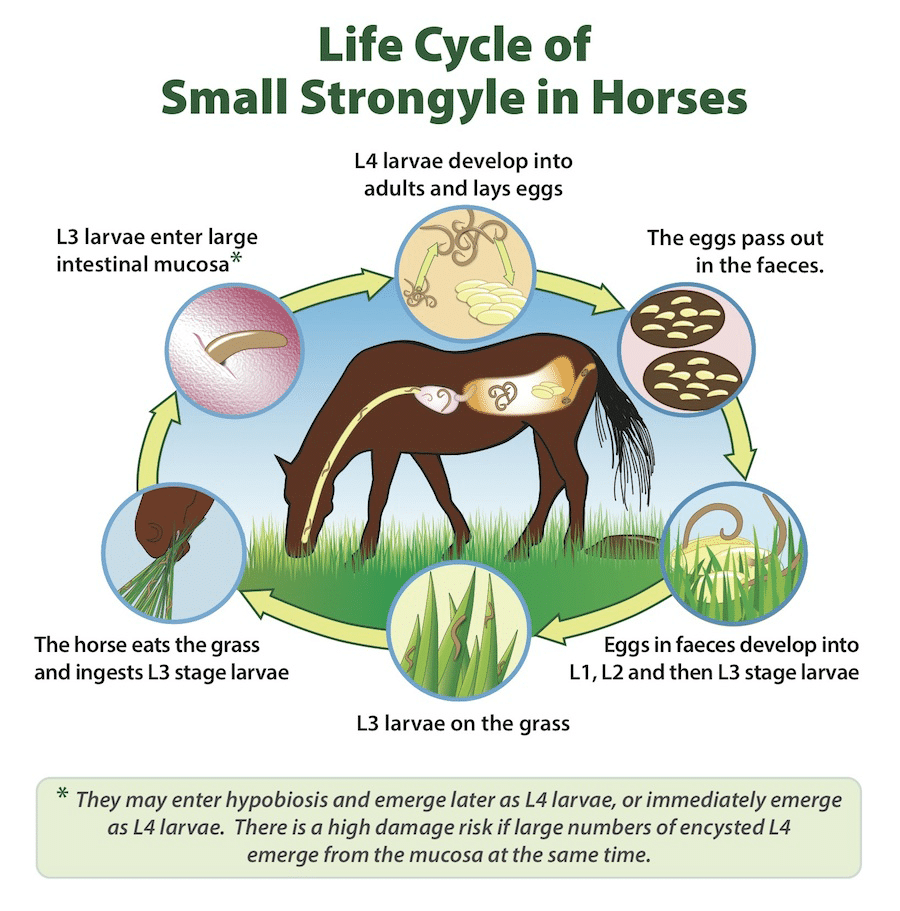

Parasites complete some of their lifecycle in the horse and some of it on the pasture. The exact lifecycle of the parasite varies by species, but as a general rule, infective larvae are consumed from the pasture by the horse whilst grazing. They develop into adults within the horse, and the adult females then lay eggs which pass in the faeces onto the pasture. Once on the pasture, the eggs hatch and the larvae undergo additional moults to develop into infective larvae which are ingested by the horse (see Figure 1).

Current recommendations

The objective of parasite management in horses has changed over the past several decades from elimination of parasitism (the relationship between the parasite and the host) to the modern approach of maintaining an acceptable level of parasitism without driving resistance. The former approach of elimination is neither achievable nor appropriate, and has come at the huge cost of widespread resistance development.

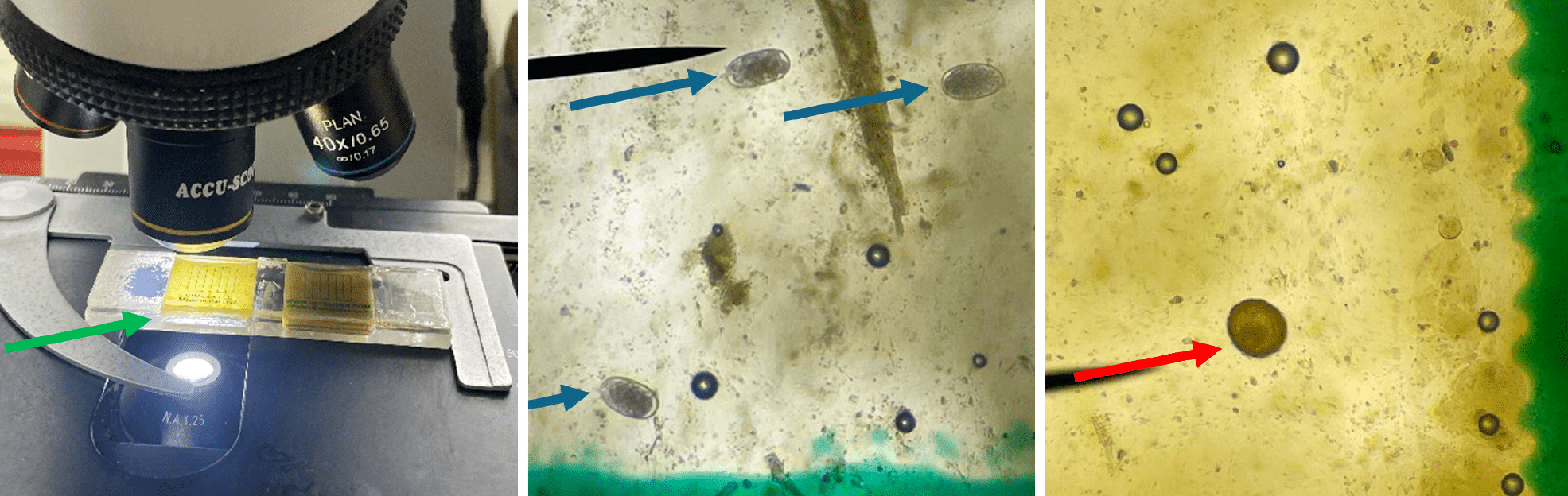

As such, interval drenching is no longer recommended. Now considered best practice, a targeted approach is used to count the number of eggs per gram of faeces (epg), allowing horses to be identified as high 500+epg, moderate 200-500epg, or low shedders at less than 200epg (see Figure 2). This enables the strategic and more frequent drenching of moderate and high shedders (in comparison to low shedders), which helps control pasture contamination and hence parasite transmission among horses.

We now know that 80% of the worms are in 20% of the horses. That is, most horses are inherently good at maintaining their parasite load at an acceptable level, while some horses (approximately 20%) are less effective at this parasite minimisation. Why does this matter? The 20% that have a high parasite load contribute large numbers of parasites onto the pasture, increasing the infectivity or contamination of the pasture, leading to more parasites that can be picked up by the same or other horses, contributing to their parasite load.

What does this mean? It means that for most horses (approximately 80%), an annual or bi-annual drench is sufficient to maintain an acceptable parasite load that is not causing the animal harm or excessively contributing to pasture contamination, while also helping to manage other parasite species such as Habronema, tapeworms and bots.

The remaining 20% of horses considered to be moderate to high shedders, may require three to four drenches annually to reduce their parasite load and the shedding of parasite eggs onto the pasture. As part of managing parasite associated disease in horses, we need to manage the level of pasture contamination or infectivity, and as such, targeted treatment of these moderate and high shedding horses provides a similar impact on pasture infectivity whilst maintaining refugia in the untreated low shedding horses.

The term ‘refugia’ refers to the population of parasites that are in refuge from (not exposed to) the anthelmintic at the time of treatment. These include parasites within a horse that has not received an anthelmintic, and parasitic larvae that are on the pasture at the time of anthelmintic administration. The parasites that are in refugia help to dilute out the resistant parasites left behind after the treatment has been administered.

What should I be doing?

Talk to your veterinarian about creating a targeted parasite management plan for your horses. The number of horses, their age, the management practices achievable on your property, and the inherent level of susceptibility to parasitism of your individual horses (high, moderate or low shedders) will determine the most appropriate parasite management plan for you. Additionally, due to the already existing widespread resistance of parasites to anthelmintics, testing the efficacy of different anthelmintics to identify products that work on your individual property may be necessary. This involves a faecal egg count (FEC) reduction test, which your veterinarian can perform. Some general recommendations include:

- An initial baseline assessment to categorise your horses as high, moderate or low shedders, which involves performing three to four FEC in a 12-month period.

- Based on FEC results, moderate to high shedders may require three to four treatments per year, and low shedders one to two treatments per year (administered during the high transmission periods of spring and autumn).

- Poo picking: removal of manure from the pasture two to three times per week reduces pasture infectivity.

- Pasture spelling for several weeks during hot weather (25-33ºC) reduces survival of infective larvae. During cooler weather this strategy may be less effective or ineffective.

- Mixed grazing with cattle or sheep can reduce the pasture parasite load.

- Don’t overstock paddocks. Aim for one horse per two hectares in non-improved pastures, or four horses per two hectares in improved pastures, plus decreasing stocking density when grass is less than 2.5cm high helps reduce ingestion of larvae and hence parasite transmission.

- Do not spread manure: this almost always increases the likelihood of ingestion during grazing by spreading the larvae.

Dr Sarah Gough is a European and Australian specialist in equine Internal medicine, and can be found at the Apiam Hunter Equine Centre in Scone, NSW.