Feeding for the discipline

What does feeding for your discipline mean, and what should you be aware of? DR JENNIFER STEWART has some expert thoughts on the subject

Despite the many and varied equestrian disciplines, every horse requires the same nutrients regardless of age, breed and discipline – it’s only the amounts that vary.

Fibre

Fibre is the foundation of all diets and all horses need to eat 1.5 to 2% of their bodyweight each day. A 400kg horse will need at least 6 to 8kg, a 700kg horse at least 11 to 15kg of hay/day, chewing for 16 hours, 4,000 times for each kilogram, and producing 40 litres of saliva a day. This protects the stomach from ulcers, the horse from cribbing, and the gut from many disorders. By comparison, each kilogram of grain or concentrate requires only 400 chews which takes approximately five minutes, putting the horse at risk of gut and behaviour problems.

Hay and pasture: Hay is just dry grass but there are important differences in nutrients once the grass becomes dehydrated to make hay. Fresh grass has high levels of vitamins, except for vitamin D, which horses manufacture in their skin. But when cut for hay, levels of vitamins B, C and E fall. Vitamin A is also lost but levels fall more slowly. Both grass and grass hay generally don’t provide enough calcium, salt, copper or zinc, and a balanced mineral supplement is the rule of thumb for pasture and grass hay diets. However, lucerne is an excellent source of amino acids and calcium.

Roughage should be 50% grass, white chaff or meadow hay and 50% legume (lucerne or clover). Early cut, soft-stemmed hay has a higher water-holding capacity, is better digested and provides more energy than late cut stemmy hay.

Beet pulp and soy hulls: Both are suitable for performance horses. Beet pulp provides as much energy as oats, is an excellent prebiotic, and can be fed at up to 1.5kg a day. Soy hulls are also a good source of fibre and can be fed at 1 to 2kg a day.

Each kilogram of roughage holds 6 to 8kg of water and electrolytes in the gut, which acts as a reservoir to replenish body fluid levels. This reservoir of water and electrolytes can be drawn upon as body fluid levels drop during sweating, which is helpful during cross country eventing and endurance rides when dehydration and electrolyte imbalances can contribute to fatigue. However, in show jumping this extra weight from gut ‘ballast’ presents the horse with an added load to carry over the jumps. Thus, for three-day events maximise roughage intake in the days before the cross country, and cut back on roughage intake for six hours before show jumping to reduce the weight handicap created by gut contents.

Protein

Protein features frequently in discussions on feeding horses. Alternately feared and revered, protein is part of the bigger picture of conditioning/nutritional protocols that result in specific changes in body composition (the power:weight ratio), performance, and muscle mass. The number of muscle cells repaired or created when horses exercise is huge. Adding to the protein requirement is red cell production (the bone marrow makes millions of red blood cells every second) and body tissue maintenance – every four days the blood platelets and most of the lining of the gastrointestinal tract are replaced, and every 10 days most of the white blood cells are replaced. Creation of new cells and maintenance of body systems all require protein.

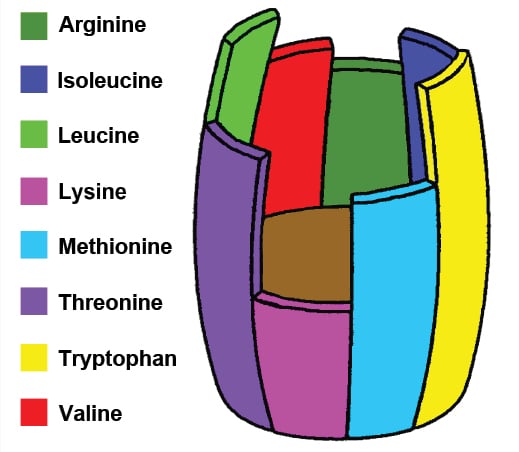

Protein is made of amino acids joined together in long chains. Every protein in the horse (eg muscle, blood cells, bone) is made to a precise and specific recipe and horses require a precise number of specific, essential amino acids. A deficiency of even one will reduce total body protein synthesis. For this reason, the total protein of horse feed is a worthless measure, unless you know the quality – in other words, the amino acid profile. For example, the feed tag might say 14% crude protein, but if all the amino acids are not supplied, to the horse it may be only 8 or 9% usable protein. Unusable protein can contribute to higher heart and respiratory rates, increased sweating and dehydration.

Poor quality protein also contributes to the gradual weakening of supportive tissues, bone and muscle. The quality of the feed protein is determined by the number and amount of each of the 10 essential amino acids. Picture a wooden water barrel (or if you prefer, a wine or beer barrel!). The barrel can only hold water, wine or beer to the level of the shortest slat. Now, think of each wooden slat as an essential amino acid (see Figure 1).

Regardless of the percentage protein of a feed, if there is not enough of each essential amino acid, a limit to protein synthesis is set, so that the other essential amino acids cannot be used and they are degraded and stored as fat. When this occurs, horses will lay down ‘cover’ (fat) instead of building muscle, blood and bone. Muscle building is so specific that if the feed meets the required levels of nine essential amino acids, but has only half of the tenth, body protein synthesis will be reduced by up to 50 per cent.

Avoid feeds with tick, faba, or mung beans as they are not well digested and increase gas and ammonia levels in the gut. Mung beans in their raw form also contain harmful compounds (cyanogenic anti-proteases) as well as vitamin E antagonists.

Energy

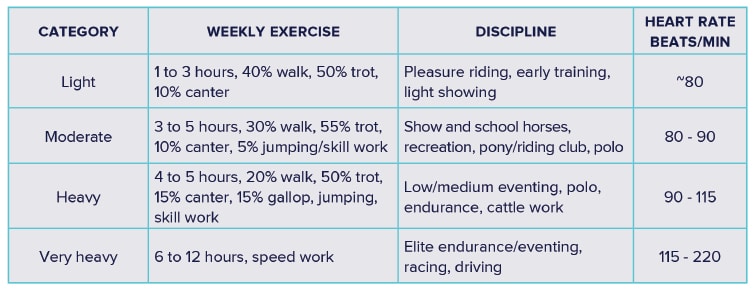

Exercise in all disciplines can be broadly categorized as light, moderate, heavy or intense, and energy requirements increase as the intensity increases (see Table 1).

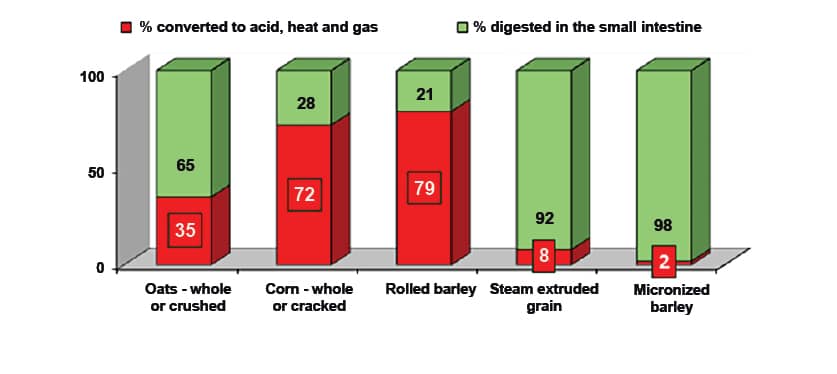

Most energy comes from fibre fermentation in the large intestine – the products of which are converted to fuel for the muscles. Sometimes as work intensity (speed or duration) increases, high energy feeds such as grains are needed. Where the grain is digested has a major impact on the amount of energy released and the risk of gut problems. Ideally grains should be digested in the small intestine but not all are (see Figure 2).

Digestion by enzymes in the small intestine releases energy, but fermentation by bacteria in the large intestine releases acid, heat and gas – all of which are unhealthy for the biome. If horses require extra energy, gradually increase grain intake over six weeks in three to four small meals each day. Seven to ten days is too fast and doesn’t allow enough time for the biome to adapt to the increased starch.

Heat-processing by extrusion or micronisation is a double-edged sword. Although they increase digestibility in the small intestine, they also increase the blood glucose and insulin levels, and this is contra-indicated for horses with or at risk of insulin dysregulation (EMS, laminitis, PPID). In addition, extruded and micronized feedstuffs produce up to 221% more lactic acid in the large intestine. If the work category means more energy is needed, oats are the most suitable grain.

Providing almost three times as much energy as grain, 500ml of oil can replace 1.5 kgs of grain. Highly digestible and with no effect on insulin, oils decrease the incidence of colic and the risk of laminitis – both of which are linked to high starch/sugar and grain diets. In terms of energy, horses fed a fat-supplemented diet have higher muscle energy stores. They also have a longer time to fatigue during exercise. Fatigue is due in part to depletion of energy reserves and is preceded and precipitated by falling blood glucose levels. Because high oil diets exert a ‘sparing’ or protective effect on blood glucose, they increase the time to fatigue.

Oil also reduces the heat load an exercising horse must dissipate. In all disciplines heat load rises as work effort increases. A tug-of-war ensues as blood is diverted away from the working muscles and sent to the skin for cooling. The reduction in muscle blood flow is a further factor causing fatigue. When the diet is 10% oil, the energy available for exercise more than doubles and heat production falls by 14% – reducing heat stress in both mild and hot climates.

It takes three to four weeks for the gut to adapt to added oils and a gradual increase is required to avoid soft manure. Metabolic adaptation of muscles to enable maximum utilisation of oils for energy may take six to eleven weeks, so sufficient time must be allowed for the benefits of adding oil to be realised. Oil also has a calming effect on excitable horses and using a high omega-3 oil (linseed or canola) helps balance the omega-3 to omega-6 ratio, reducing body inflammation. Incorporation of omega-3 fatty acids into red blood cell membranes improves red cell flexibility, increasing blood flow through narrow capillaries in the lungs and muscles and improving blood oxygen levels. Finally, inclusion of oil (8 to 10% of the diet) and exclusion of high starch/sugar feedstuffs can ameliorate the risk of muscle disorders such as tying-up. For each 100ml of oil added to the diet, 100mg/iu of vitamin E is required to counter the oxidation and free radical production that occurs when oil is burned for energy.

OilFeeding before, during and after exercise

When complete feeds are not fed at recommended rates, vitamin and mineral intake is sub-optimal. In increasing the amount of complete feed to meet the increased vitamin and mineral needs associated with exercise and training, horses can become fat. Feeding a correctly formulated amino acid/mineral/vitamin/antioxidant supplement daily, rather than a complete feed, allows you to use various strategies to support performance and recovery.

For all horses, an empty stomach is a major risk for gastric ulcers. Even at a walk there is splashing of stomach acid. The amount increases with speed, but all horses need 0.5 to 1kg of roughage before exercise. Lucerne with its high calcium and protein content is an excellent acid buffer.

For endurance horses, feed 1 to 2kg of soft-stem hay one to three hours before the event starts, plus 70g of a 3:1 mix of sodium chloride (salt) and potassium chloride (light salt). Lucerne has a high calcium content and when fed daily it can suppress parathyroid responsiveness. Blood calcium levels fall during a ride and the parathyroid hormone responds in minutes to release some calcium from the skeleton. If the horse has a calcium-rich diet in the seven to ten days before a ride, the parathyroid hormone may not respond quickly enough when required during the ride. Many riders withdraw lucerne in the week leading up to a ride and reintroduce it just before, during and after.

For disciplines where horses exercise for long periods or long distances (endurance, cross country), dehydration and electrolyte loss can precipitate fatigue. Hay intake should be high before a ride to increase the reservoir in the gut. During the ride, pellets of roughage can be consumed faster than hay. They reach the hindgut more quickly, fermenting rapidly to increase energy supply. For show jumping where performance weight can be a handicap, roughage should be reduced for six hours before an event.

Falling blood glucose causes fatigue in muscle and in brain function. Grains should not be fed less than four hours before starting exercise to allow time for blood glucose to stabilise.

After heavy and intense exercise, refuelling is the goal and we need a rapid rise in blood sugar and insulin. This is the time to feed a small amount of oats or extruded grain hourly. Adding a protein/antioxidant supplement plus a tablespoon of salt will promote drinking and rehydration.

Dressage horses don’t need a high level of cardiovascular fitness compared with eventing, racing or polo. Suppleness and strength, however, are extremely important. Correct amino acids (a supplement and soy meal) and a slow, cool supply of energy (oils, beet pulp, early cut hay) support tendon and ligament strength and the muscle response to training.

Genetics sets the limit to performance, but nutrition is a powerful tool when used properly. How closely an individual horse approaches that limit, is ultimately determined by training and nutrition.

Dr Jennifer Stewart BVSc BSc PhD is an equine veterinarian, a member of the Australian Veterinary Association and Equine Veterinarians Australia, CEO of Jenquine and a consultant nutritionist in Equine Clinical Nutrition.

All content provided in this article is for general use and information only and does not constitute advice or a veterinary opinion. It is not intended as specific medical advice or opinion and should not be relied on in place of consultation with your equine veterinarian.