Your horse’s eye health

The health of our horse’s eyes is as important as our own, and this article from DR CAT MARSDEN makes for informative and interesting reading.

It’s not uncommon for vets to be called out to a horse with a sore eye. The position of the eye and horse’s flighty disposition can often predispose them to eye injuries. Typical signs of a painful eye include;

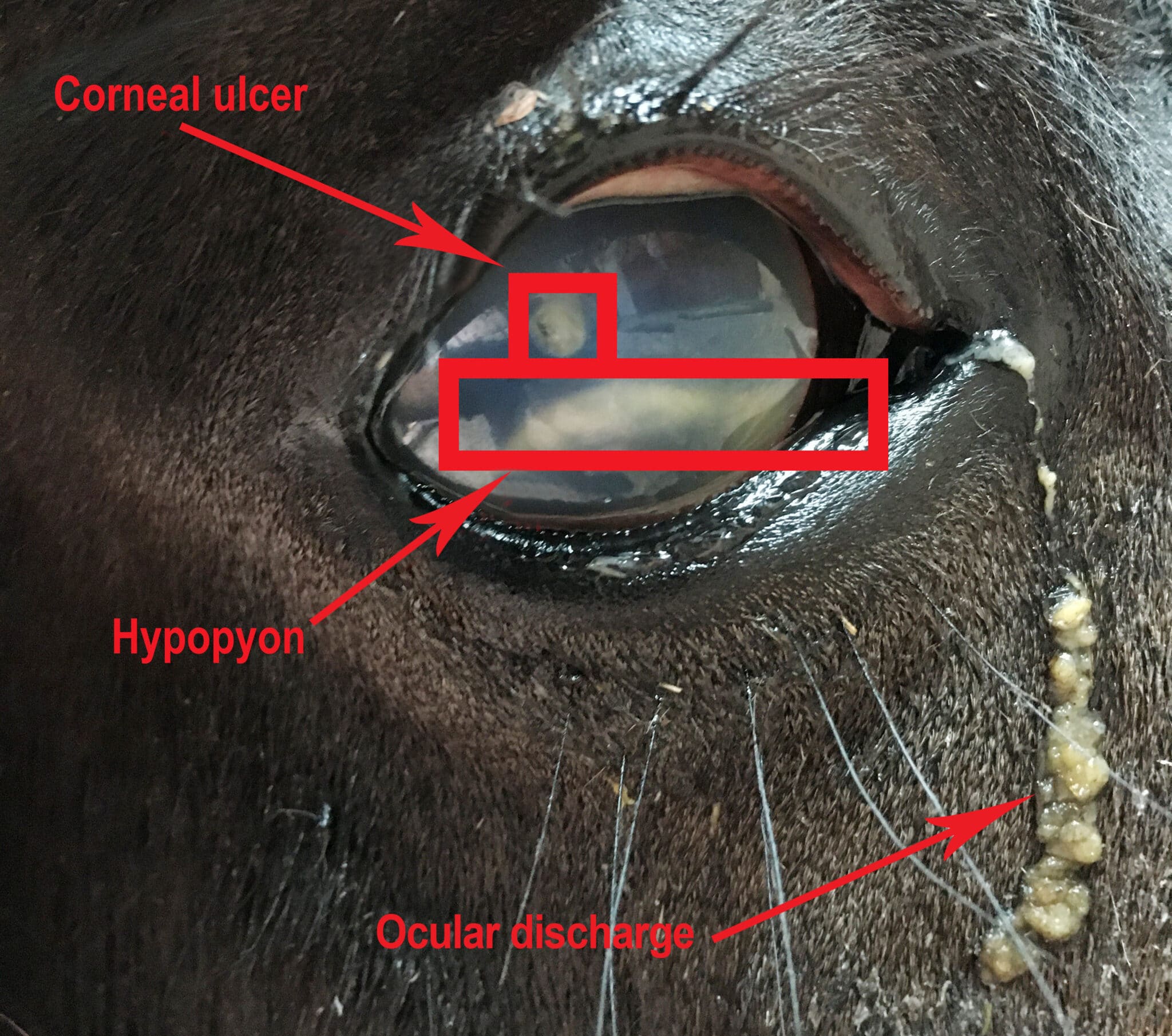

- Ocular discharge (eye mucous)

- Photophobia in which the eye is closed up or squints due to a sensitivity to light

- Swelling around the eye

- Corneal oedema (a cloudy appearance to the eye)

- Reddened appearance of the conjunctiva, the transparent mucous membrane that lines the inner surface of the eyelids and (with the exception of the cornea) the outside surface of the eyeball.

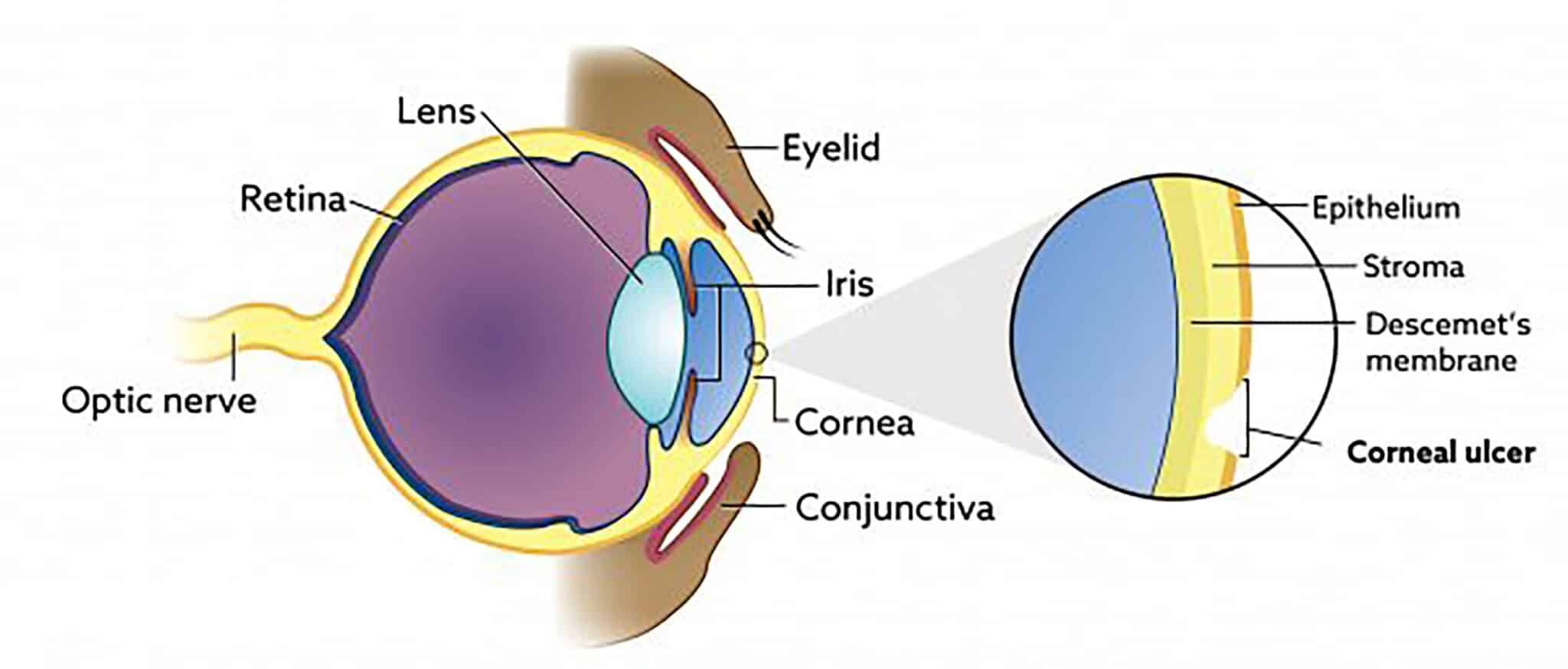

The most common cause of a painful eye is a corneal ulceration, an open sore on the cornea. This is caused by trauma to the outermost surface of the eye, causing loss of the most superficial surface of the cornea. The cornea in horses is approximately 1mm thick and as such, is very easily traumatised. If the ulcer is simple and superficial (shallow), it should heal within seven days with minimal scaring. However, equine eye ulcers can rapidly become infected, which is considered an emergency. If left untreated, an infected corneal ulcer may form a melting ulcer (when the cornea becomes soft and jelly-like), a descemetocele (a protrusion in one of the layers of the cornea), or may even cause the eyeball to rupture. As such, if you notice any of the clinical signs listed above, you should call your vet immediately.

To diagnose an eye ulcer, vets will typically perform a thorough clinical examination, focusing primarily on the painful eye. A dye will often be placed in the eye to highlight the area of ulceration and allow your vet to establish its depth. Once there is a clear understanding of the nature of the ulcer, an appropriate treatment regime can be established. Typically, this includes ointments for use in the eye as well as oral pain relief.

Although eye ulcers can heal quickly, they can also deteriorate rapidly. If your horse is being treated for an eye ulcer, it’s crucial that you monitor their progress carefully and keep your vet informed if there is any deterioration, an increased degree of pain, increased corneal oedema, or increased discharge.

If your horse is experiencing pain in their eye, here are some useful tips to follow:

- Call the vet – just like our own eyes, your horse’s eyes are precious, so waste no time in getting expert help.

- Horses with injured eyes are often sensitive to light. If possible, move your horse into a stable or shaded paddock prior to the vet arriving.

- Don’t put any ointment in the eye. There are lots of different ointments for eye issues in horses, and some can make ulcers worse rather than better.

- Horses often rub at sore eyes – you may need to supervise or distract your horse prior to the vet’s arrival to prevent them rubbing and further irritating the eye.

- Do not clean away the ocular discharge. The colour and quantity of discharge from your horse’s eye can give your vet vital information and assist them to formulate an appropriate treatment plan

- Note any injuries visible to the eyelid or the eyeball itself.

Raffy the Shetland

For a deeper insight into the way a horse’s eye problems are diagnosed and treated, you may find this case study of Raffy the Shetland Pony interesting. Raffy was five years old when his owner noticed he had a cloudy right eye which was light sensitive. She initiated treatment with an old eye ointment she had left over from a previously sore eye, but after five days and no improvement, she called me and asked for me to come and have a look.

On initial examination, Raffy was sedated and two nerve blocks were administered to desensitize his eye and remove his ability to squeeze his eye closed. When I noticed pus in the anterior (front) chamber of the eye, a condition known as hypopyon, it very quickly became apparent that Raffy wasn’t suffering from a simple corneal ulcer.

Hypopyon is a condition that occurs when bacteria enter through the damaged corneal surface and an influx of inflammatory cells become trapped within the eye’s anterior chamber.

My next step was to apply fluoresceine stain (a dye) to the surface of the eye, which confirmed my original diagnosis of a corneal ulcer. To understand how fluoresceine works, it’s useful to know that the cornea has multiple layers and some of these layers repel water (hydrophobic) and some of them bind to water (hydrophilic). The outermost layer of the cornea is hydrophobic – which is why your eyes are moist and teary. The second layer of the cornea, however, is hydrophilic. Fluoresceine is able to bind to the hydrophilic layer of the cornea, and applying this stain allows the vet to identify whether or not the cornea is damaged and if so, how extensively.

Finally, poor Raffy was also diagnosed with uveitis. Put simply, this is an inflammation of the uvea, the vascular and pigmented structures of the eye. The clinical signs of this are typical of a painful eye – cloudiness, sensitivity to light, ocular discharge, and a constricted pupil.

Treating Raffy required a multimodal approach. I prescribed two types of antibiotic ointments to go into his eye, in addition to topical atropine to help resolve the uveitis, and I also started him on oral pain relief and doxycycline, an antibiotic that is released in tear film. After a few weeks of four times daily treatment with eye drops, and twice daily oral medications, Raffy’s eye was fixed!

Luckily, Raffy tolerated all his treatments well. However, if he hadn’t, the next step to consider would have been putting in place a sub palpebral lavage (SPL). This is essentially a catheter for the eye that delivers liquid medication into the tear film through a long tube that runs from underneath the eyelid, up between the ears and down the mane. An SPL allows treatment to be administered into the treatment tube and removes the need to fight to pry the eye open. It’s a great option for difficult to manage patients, but because complications can occur it requires stabling and very observant and proactive owners.

If you haven’t already guessed, there’s a moral to this story: don’t wait to get your horse’s eye examined by a vet if there is an injury or signs of pain. Early intervention is always best, and a speedy resolution is often achievable if the correct treatment is initiated early.

Dr Cat Marsden’s particular interests are in equine sports medicine, lameness and reproduction. She can be found at Southwest Equine Veterinary Group in Warrnambool VIC.