It was once widely believed that the modern thoroughbred was created through the merging of three stallions with ‘Arabian’ bloodlines with that of around 100 so-called ‘royal mares’, (who were incorrectly assumed to have been of mainly Arabian blood). Recent genetic testing has dispelled these myths.

Horse racing as a sport has probably existed since humans first domesticated wild horses around 6000 years ago. Racing has always been a significant part of Nomadic culture, and Ancient Etruscans Greeks and Romans were famous for their chariot and mounted horse racing events.

King William of Scotland enjoyed watching races over the Lanark moor in the twelfth century, and Henry VIII organised English horse races during his reign in the early 1500’s.

Contemporary horseracing can trace its origins to the British Isles, with the horses of choice being English Running Horses, Scottish Galloways and Irish hobbies, who were ridden in match races where gentlemen, and military officers would wager privately on the fastest horse. Over the centuries, the practice of betting on horses expanded. Multi- horse races became a professional sport and racecourses opened up all over England with increasingly large incentives to attract the best horses. These sizable rewards made the sport of racing economically profitable, and the sport spread rapidly throughout Britain.

Three Foundational Fathers

When we think of the bloodlines that most influenced the modern racehorse (particularly when it comes to speed) three names instantly come to mind: the Darley Arabian, Godolphin Arabian, and Byerley Turk. These founding fathers were imported into Britain by aristocrats looking to breed faster horses, and local lore has always purported that these stallions were of Arabian breeding.

Writers and historians have long theorized the congruence between Thoroughbred and Arabian bloodlines.The similarities between thoroughbreds and Turkoman descendants like the Akhal-Teke have always been difficult to ignore.

The late Alexander Mackay-Smith expressed his doubts about the true genetic origins of the Thoroughbred in his book “Speed and the Thoroughbred: The Complete History.” Historian Peter Willett also mused that the modern Thoroughbred seems to contain “some ingredient other than the pure Arabian.”

Many horses were appropriated from Turkish officers from the Ottoman empire, and the writer Jeremy James notes “the Ottoman Empire produced fabulous horses of great variety, of which Arabs formed one part, but the vast majority of military horses used by the Ottoman Turks were of Turkish origin.”

Turkoman cavalry horses were required to carry heavy loads over long-distances at speed. They were selected for demonstrating the same traits that English breeders sought in racehorses: stamina, speed, and hardiness. Though thoroughbreds share many features with Arabian horses, they are taller, more angular, with a head that lacks the concave bone structure of an Arabian.

Recent genetic studies dispelled the myths about the original thoroughbred gene pool, revealing once and for all the existence of two genetic sub-groups that split from the same ‘oriental’ root centuries ago. The southern sub group of Oriental horses comes from Central Arabian peninsula (Arabian) while the northern group originates from the Central Asian steppe (Turkoman horses). Despite what their names suggest, all three of the ‘Arabian’ foundation stallions has Turkoman sub-group lineages.

A further study published in the journal Scientific Reports found “no significant genomic contribution of the Arabian breed in the Thoroughbred racehorse, including Y chromosome ancestry.” Modern thoroughbreds share just 8% of their genes with Arabian horses, and 31% of their genes with Turkoman horses.

So how did the history books get it so wrong?

During the 16th and 17th centuries horses changed names as they changed owners, and therefore many ended up with the same name. Some horses appeared so frequently in breeding records they could not possibly all reference the same horse. Furthermore, an identification system was devised where imported stallions were given names to define their country of origin – so if a horse was imported from Arabia, he was designated an “Arabian” regardless of his bloodline.

It is probable that since the three founding stallions came from the Middle East (the Byerly Turk was appropriated from a Turkish officer, the Darley Arabian from the sheik in Syria, and the Godolphin Arab was said to have arrived in France by way of Tunisia), the horses were identified as Arabian rather than Turkomans.

The Byerly Turk was the prototype of Turkoman warhorse, and his Turkoman origins were no little surprise to thoroughbred historians. After he was captured from the Turks in the Battle of Buda (1686) the stallion served as Captain Byerley’s war horse at the Battle of the Boyne (and was the only foundation sire that ever actually raced) before commencing his stud duties in England.

Byron Rogers, from Bloodhorse magazine, believes the Darley Arabian may have been of the Muniqui horse population, which was known to have been crossed with Turkoman stallions during the 17th century. This would explain the Y-chromosome appearing in his genealogy. Thomas Darley, after purchasing the horse, sent a letter to his brother where, he explained that “the colt was from one of the purest of Arabian strains, and his name was Manak or Manica” – which may have been a reference to the ‘Muniqui’ strain of Arabians, which were likely crossbreds of Arabian and Turkoman types.

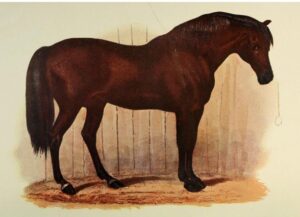

The Godolphin Arab, is the stallion with the most obscure past of all three (legend has it he was found pulling a water cart on the streets of Paris). Rogers muses how the Godolphin Arab was described as being a ‘gold-touched bay’ a trait that was also apparently passed down to some of his offspring. This metallic sheen is often seen in modern-day Turkoman descendants like the Akhal-Teke.

At least maternally, the English thoroughbred is actually, very English (well, British).

Until recently, the exact origins of the thoroughbred’s maternal lines were equally unclear, as record keeping during the early foundation stage was often inaccurate, or nonexistent.

What we do know, is that they were the creme de la creme of a closely supervised breeding programme at the Sedbury stud of the D’Arcy family. They were likely Irish Hobbies, English Running Horses and Scottish Galloways.

Recent genetic studies have confirmed that these mares had only faint Barb and Arabian influence over the centuries and today thoroughbreds share 61% of their genes with breeds like the Connemara, Highland Pony, Irish draft and Fell Pony.

The Galloway pony stood between twelve and fourteen hands in height, and its modern-day descendants are the Highland and Fell ponies which roam the moors and mountains of Scotland today. Originating in the highlands, these little horses showed remarkably stamina, especially when required to cover long distances in difficult weather conditions. They were reported to be spirted, strong and able to ‘amble’, or pace.

The Irish Hobby was the ancestor of the modern Connemara pony and the Irish Draft Horse. Quicker and more agile than the Galloway, in Scotland they were used during the War of Independence by Robert the Bruce for his mounted assaults against King Edward I and his men (sometimes requiring the Scots ride up to 120 km a day). The King of England went as far as banning the Irish from exporting horses, just to prevent these swift animals from falling into his enemies’ hands.

Celtic ponies have been shown in genetic studies to share a common ancestry with British native ponies. It is thought that the first horses to arrive in the British Isles were Celtic ponies, who arrived with the Phoenicians on ships, and were used to mine tin. There is a theory that Iberian horses introduced a second time around the 1500’s, when a ship from the Spanish Armada went down off the coast – but this theory is unproven.

Celtic ponies are naturally gaited, and they probably spread the gait-keeper gene mutation to the British Isles. In a recent study, researchers genetically examined horse remains all over Europe, and found that the earliest appearance of the gaited gene occurred in horses from England (circa 850 AD). The gait-keeper gene is what causes horses to amble/ pace at remarkable speed – and was often mentioned as a feature of both the Irish Hobby and the Scottish Galloway.

Irish and British horses were often transported to Iceland, and the Vikings cultivated the fifth gait (tölt’) that appeared in their war horses. Today it is one of the Icelandic horses most endearing performance traits.

The Royal Mares were likely the descendants of the fastest of these Irish Hobbies and Scottish Galloways. When these early racehorses were exported to the New World, they helped spread the gene to the ancestors of modern-day Standardbreds, and other gaited breeds such as Saddlebreds and Paso Finos.

The Genetic Legacy Of Speed

In 2010, a group of researchers from the UCD led by Dr Hill established that a variation of the myostatin gene (the speed gene) could predict athletic race performance and muscle development in thoroughbred horses. This genetic mutation (which is also seen in greyhounds) is the most important genetic contributor to predicting inherited potential for racehorses. The gene mutation can predict a horse’s race distance aptitude, skeletal muscle growth and potential to develop fast-twitch muscles suitable for quick bursts of speed. The gene was introduced into the thoroughbred gene pool circa 300 years ago, around the era of D’Arcey’s ‘Royal Mares’.

A 2012 research paper led by Dr Emmeline Hill, a scientist at University College Dublin (UCD) discovered that the same speed gene mutation present in thoroughbreds, was also prominent in Scottish Shetland ponies.

Researchers traced the origins of the mutation by screening genomic material sourced from living and dead horses. Elite racing performers of the past and present were part of the study (using skeletons held in museums) to understand more about the mystery contributor of the the speed gene. It is thought she was a native British horse, the ancestor of one of the first thoroughbreds.

While researchers don’t know which of the old breeds deserves the honour of being the original myostatin mutation contributor,we do know that the gene was in one or more of the royal mares, and that horse was in some way related to the modern day Shetland pony, so it is highly probably this horse was either a Scottish Galloway or and Irish Hobby.

Big Hearts Often Mean Big Wins

Speed is crucial to a racehorse, but so is a big heart. To sustain long distances at tremendous speed, the volume of blood pumped with each horses heartbeat rises by almost 50%. Therefore, the only way to meet the heart’s demands for oxygen and nutrients is an above average sized heart…

When Secretariat died in 1989, his post-mortem autopsy revealed that he carried a heart that weighed a whopping 10 kilograms. Secretariat’s enormous heart inspired the American researcher Marianna Haun to investigate further. She wrote a book on why some racehorses (including legends such as Phar Lap and Eclipse – Featured Image) were born with an oversized heart 1.5-3 times that of a normal horse, and set out to prove that the large heart genetic mutation could be traced back to a unique gene mutation (the X factor) from a single female ancestor. Her investigations took her back to a mare in the 1800’s named Pocahontas, who was related to Eclipse.

Additional studies followed, and these went further back, eventually tracing the mutation all the way to the dam of a horse foaled in 1690 named Hautboy. This mare, who was the end of the line for researchers, was again, one of D’Arcy’s Royal Mares, suggesting the same maternal lines that hold the key to speed, may also hold the secret behind inheritably large hearts in racehorses.

NB. The X-Factor theory has never been scientifically peer-reviewed, and the genes associated with heart size and athletic performance have not been scientifically identified, nor have the mode of inheritance been determined; a large heart may be influenced by several different genetic factors

Time To Start Championing Native Breeds Again

Today the thoroughbred is one of the most populous horse breeds in the world. Without the genetic contribution of the thoroughbred, we would have no American Quarter Horses nor Standardbreds.

The thoroughbred continues to influence modern sport horse breeding, with approved stallions and mares are regularly used in the Trakehner, Westphalian, Danish Warmblood, Dutch Warmblood, Holsteiner, and Hanoverian and Italian Maremmano breeding programs to provide genetic diversity.

Discovering that the founding fathers of modern-day racing were not Arabian at all, but instead Turkoman, would have been a bitter pill to swallow for many pedigree historians who had debated with critics on the Arabian inheritance for decades. But in the end, Arabian and Turkoman horses are still closely related, and the two sub-groups share many of the same traits and features (including speed, stamina and elegance). What is really fascinating, is what genetic testing has brought to light about the maternal heritage of thoroughbreds.

While oriental breeding stallions have long been championed and praised for their invaluable contributions to equine bloodlines all over the world, many native breeds have often had their contributions forgotten.

The mysterious and often forgotten ‘Royal Mares’ were not influenced by Arabian breeding as previously thought, but instead were likely the descendants of Celtic ponies shipped to Britain centuries ago. Close relatives to Irish drafts, Shire’s, Connemara’s and other British and Irish breeds.

With the advent of modern genetics, we now know that a native horse was the original contributor of the speed, and that the gait-keeper gene that gave Standardbreds and Icelandic horses their unique gait also originating in Britian. Science is yet to prove that the large heart gene (seen in horses like Phar Lap and Secretariat) is genetically heritable, but if it does, and I am sure it will, my bets are on that the original contributor will be a British bred mare too!

Sources and further reading.

Books:

Mackay-Smith, A. (2000). Speed and the Thoroughbred: The Complete History. United States: Derrydale Press.

Landry, D. (2008). Noble Brutes: How Eastern Horses Transformed English Culture. United Kingdom: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hyland, A. (1998). The warhorse, 1250-1600. United Kingdom: Sutton.

Jockey’s Guild – History of Race Riding. (1999). United States: Turner Publishing Company.

Research Papers and Articles:

Galopin – New Research and an answer to an old question, by Bryon Roger

The Irish Hobby – the genetic source of modern equine sport

Mitochondrial DNA and the origins of the domestic horse

Genome Diversity and the Origin of the Arabian Horse

Y Chromosome Uncovers the Recent Oriental Origin of Modern Stallions