Equine nutritionist LARISSA BILSTON offers up a comprehensive roughage, forage and fibre guide.

Roughage should form the foundation of every horse’s diet. Depending on plant maturity and quality, it provides the majority of their requirements, including most or all of a mature horse’s protein requirements, and often enough calories to maintain body condition. It is often the overlooked but much needed key ingredient for weight gain. On the other end of the scale, people caring for overweight or insulin resistant horses are very aware of the need to limit pasture access, providing low sugar roughage to keep their horses healthy.

Why is roughage important?

The first rule of good horse nutrition is to feed plenty of fibre-rich roughage because the horse gut evolved to continuously ingest and digest fibre. The minimum amount of roughage required is 1% of their bodyweight in dry matter. Horses with access to lots of fresh pasture will graze for most of the day and consume their daily requirement. They will also drink less water when grazing lush pasture because of its high water content.

Unfortunately, horse owners rarely have access to unlimited good quality pasture, and many horses kept in over-grazed paddocks, stables and yards don’t get enough roughage. Under these circumstances, they must be fed preserved grass in the form of hay, silage or chaff to remain healthy. Hay-reliant horses can consume their daily dry matter requirement in a relatively short period of time. Ideally, they should have access to roughage at least 20 hours a day – there can be severe mental and physical health impacts when they do not get enough.

Because horses evolved with constant access to grazing, the horse stomach secretes acid continuously. When acid is secreted into an empty stomach, the build up can lead to gastric ulcers, diarrhea, pain-related bad behaviour and colic. Horses become anxious when left without food, and release ‘happy hormones’ during grazing. Feeding adequate roughage is also important for maintaining a healthy population of gut microbes. Important for general good health, gut microbes not only aid digestion by producing enzymes, vitamins and nutrients, they also produce molecules critical for effective functioning of the immune and nervous systems.

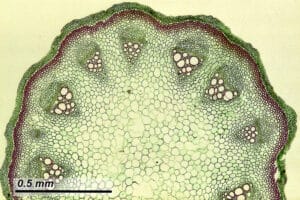

A microscopic view of a plant stem in cross section.

What’s the difference?

Roughage and forage are terms used interchangeably to describe the grasses and plants horses graze in fresh or preserved forms. This includes fresh pasture, hay, chaff, chaff cubes, haylage, baleage and silage.

Fibre, the structural components of plant cells, is made of cellulose, hemicellulose, pectin and lignin. The cells in young, leafy grasses have relatively thin cell walls, but as the plant ages the cell walls in the stem strengthen to become the plant’s ‘skeleton’. Flowering grass plants produce strong stems to carry their flowers, so the fibre content is higher in flowering and seeded plants than in young, leafy plants.

Horses cannot digest cellulose, hemicellulose and pectin in the foregut (stomach and small intestine) because they cannot produce the enzymes needed to break down these very tough fibre components. Instead, they rely on the beneficial microorganisms in the hindgut (mainly the cecum) that are able to break fibre down into volatile fatty acids available for the horse to digest.

Choosing a roughage source

Roughage usually contains at least 18% fibre, most of which is indigestible to the horse without the aid of the gut microbiome. The most common forms of roughage in Australia are pasture, hay or chaff. Don’t confuse ‘super fibre’ feeds, such as soy hulls and beet pulp, with roughage. Super fibres contain fibre which the horse is able to digest itself, making them healthy, cool fuel alternatives to grain hard feeds, but not a forage replacement.

Horse owners rarely have access to unlimited good quality pasture.

When grass is in short-supply, free choice grass hay is the best replacement unless your horse is on a weight loss or low sugar diet. The addition of a kilogram or two of lucerne hay provides a wider variety of amino acids. Limit lucerne or clover hay to under one third of total forage intake because of its very high protein content. Ideally, provide more hay than chaff because the long stems encourage more chewing, which creates more saliva to buffer stomach acid. Feeding a variety of fibre types and forms is good for the gut’s microbial diversity. However, these guidelines should be modified if you are feeding an insulin resistant or laminitic horse or pony. These need a low starch, low sugar hay and may benefit from a small amount of lucerne or quality protein to aid recovery. Limit total intake to 1.5% of bodyweight for weight loss.

Hay can be fed in multiple piles around the paddock to stimulate more natural grazing (preferably on a mat to prevent sand ingestion), in large round bales offered free choice, or in slow feeder hay nets to help make the hay last. The key is to make sure your horse never goes more than a few hours without something to eat.

How much should I feed?

As a rule of thumb, horses should consume between 1.5% and 2.5% of their body weight in total feed per day – that’s the feed’s dry matter content, not counting moisture. Whenever pasture levels are low or grasses are dry and stalky, horses need to be fed hay. They require a minimum of 1% of their body weight as dietary forage and most require closer to 2%. When grass is not available, a 500kg horse needs 10-12kgs of hay daily, 5-6kgs for a 250kg pony.

If your horse loses weight during competition season or when they’re in work, despite having free choice access to plentiful, good quality (leafy) grass or meadow hay, you’ll need to add a concentrate or hard feed. The amount of hard feed can and should be varied to maintain weight at the required level. Seasonal changes in grass quality and variation between the calorie content of hay batches can necessitate adjustment to the amount of hard feed even when there’s no change to the work level.

A horse at rest should consume 80-100% of their daily intake as roughage, in light work 65%, and in moderate work 55-65%. Horses undergoing intense training may only have enough capacity to consume 40-50% of their daily intake as roughage due to their high consumption of energy feeds (grains/oil). Pregnant, lactating and growing horses may also need a protein supplement to provide the necessary levels of essential amino acids, especially lysine, methionine and threonine.

Easy-keeper horses and horses needing to lose weight should be limited to 1.5% of their bodyweight in dry matter daily, mainly forage with just a token feed to provide the essential vitamins, minerals and omega-3s needed to balance the forage and meet requirements.

Balancing a forage-based diet

Hay contains most of the minerals, protein and calories present in the pasture from which it was made. But in drying grass to make hay, it loses much of the original vitamin and healthy omega-3 fatty acid content. The vitamin levels in hay decline rapidly with storage and 12 month old hay has virtually no vitamins, although it will retain the minerals it had when harvested.

Fresh grass contains around four times as much omega-3 oil as omega-6. Omega-3 is a fragile molecule easily destroyed if exposed to heat, oxygen or light (as in the hay making process), whereas omega-6 molecules survive. Thus hay-reliant horses need a supplementary source of vitamins and omega-3 fats as well as minerals and salt to balance the rest of the intake and optimize their health and performance.

Larissa Bilston, BAgrSc (Hons) is the Equine Nutritionist for Farmalogic.

Feature Image: Ensure your horse never goes more than a few hours without something to eat.