Reducing recovery time

Recovery from exercise is as important as training and competition, and the recovery routine needs careful thought and planning, writes DR JENNIFER STEWART.

Preparation for the next work session begins as soon as the last one finishes, and the recovery routine needs as much thought and planning as the training program.

Recovery after exercise has different components: respiration, body temperature and heart rate all recover rapidly, while others such as the immune, digestive and musculoskeletal systems can take days or weeks.

Depending on exercise intensity, duration and recovery strategies, the respiratory system and energy stores in the muscles and liver recover within 24–48 hours; digestive function within 2-3 days; hydration and electrolyte balance 5-7 days; muscle repair 7-10 days; up to 2 weeks for the immune system to recover; and 3-4 weeks for bone, tendon and joints to recover (assuming that there’s no actual injury).

One of the first things we usually do after exercise is to allow the horse to cool down. What happens during this period? Body temperature, respiration, heart rate and blood lactate return to normal. Monitoring skin and/or rectal temperature during recovery is important. The increase in body temperature depends on the workload and weather (temperature and humidity). To recover in mild, dry conditions may just require 15–20 minutes of walking. In warmer or humid weather we may need cold water, and in hot/humid conditions, ice water, showers, fans and misters.

It was once believed that cooling the large back muscles (gluteal and biceps muscles) caused muscular problems but cold water only affects skin temperature, not the deeper tissues. Rolling is also helpful for reducing heat load by transferring heat from the body to the ground and significantly reducing body temperature. Coat colour impacts body temperature with black hair absorbing twice as much heat as white/grey.

Cold water is more efficient for cooling than tap water. However, preparing cold water in hot and humid conditions requires a lot of ice or refrigeration. Recent studies leading up to the Tokyo Games compared several cooling methods: 30 minutes walking; walking in front of fans producing an air current of 3.0 m/s; walking with the intermittent application of 10°C cold water with and without scraping; and standing the horse under a shower of tap water at 26°C. Standing still under a shower resulted in the most rapid decrease in core temperatures (9 minutes); walking produced little decrease over 30 minutes; walking plus fans 15 minutes; cold water without scraping 11 minutes, and with scraping 13 minutes. Continual application of running tap water offered the most effective method to decrease core temperature. The essential feature is not the water temperature or the use of scraping, but that the water temperature is lower than the body temperature.

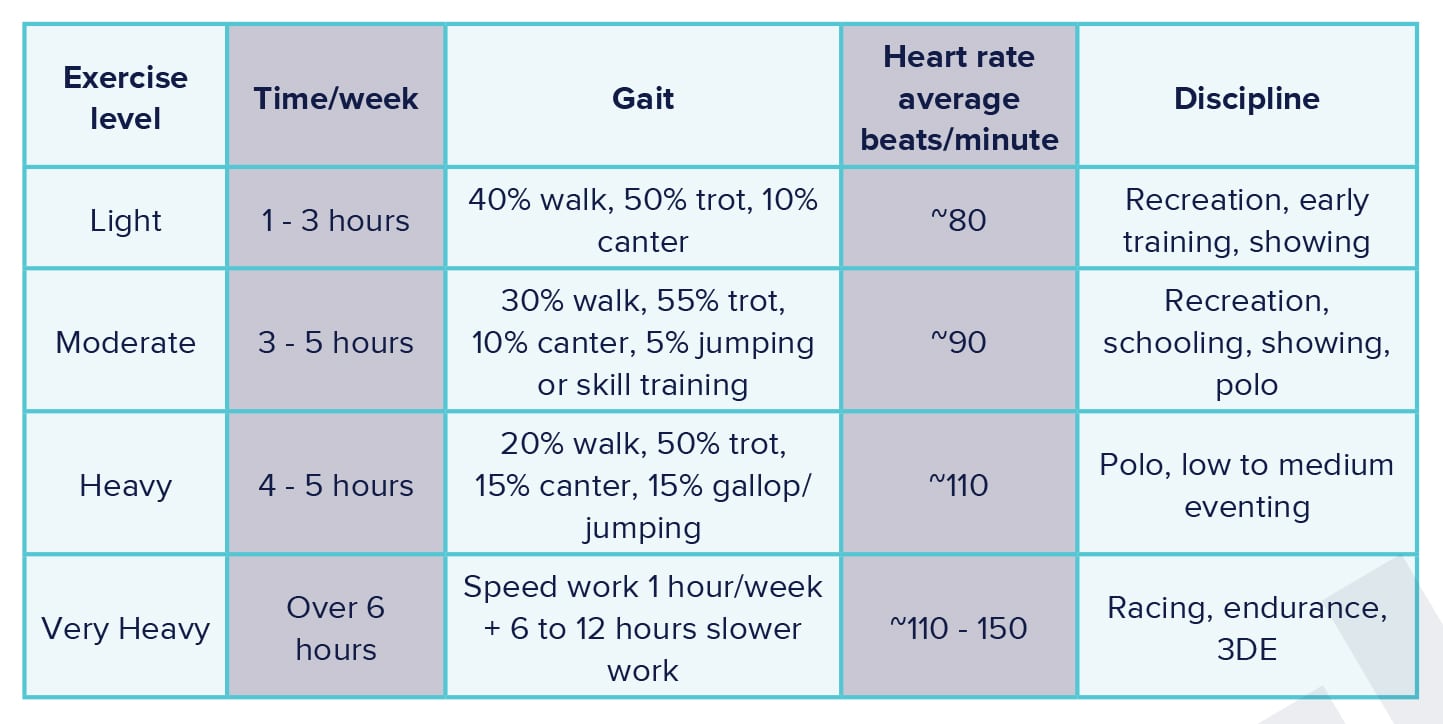

After heavy, more intense exercise. cooling down requires different recovery strategies (refer to the chart) as it results in lactic acid accumulation. Instead of walking, these horses often need 15 to 30 minutes trotting at 250 metres/minute at a heart rate of 100 to 120 beats to reduce acid levels.

As well has bringing in oxygen, the respiratory system is involved in body temperature regulation. Horses breathe 6-18 times per minute and move around 80 litres of air. This triples at the walk and may increase 10-fold, moving 1,800 litres per minute during exercise. When training matches the fitness level of a fit horse, this should return to 40–50 breaths per minute after 15 minutes recovery time. The heart rate is usually 4 times the respiratory rate and if respiration rate exceeds the heart rate, it needs investigation.

Heart rate recovery is an important measure of how well a horse is coping with the work. You want a horse to recover to a heart rate of 60-64 bpm within 15 minutes of recovery. Fit horses generally reach this level within 2 to 3 minutes, and at least within 10 minutes. Endurance and cross-country horses in good condition reach heart rates of up to 200 beats per minutes and recover to below 70 within 10 to 15 minutes.

If the heart rate doesn’t recover, the horse might have worked too hard, be developing metabolic disturbances, dehydration, or musculoskeletal pain. Heart rate monitors provide real-time feedback on a horse’s exertion level, helping you to avoid undertraining or overexertion. During recovery, they provide a key indication of the fitness level. A rapid return to resting heart rate (ideally reaching 120 bpm or less within 2 minutes post-exercise) signifies a high level of fitness and indicates the horse’s readiness for subsequent training or competitions.

Walking during the cooling period allows muscle to relax and return to their normal resting length and tension. Stretching is also recommended as part of warm-up and cool-down routines, important for all horses especially those stalled or stabled. These horses do not have the opportunity to graze, flex, and extend joints through their full range of motion and if the exercise program isn’t based on cross training many muscle groups may rarely be engaged, if at all. Anyone can learn to effectively and safely stretch a horse. Daily stretching can be too intensive for most horses, and three to five stretches, three to five times a week is ideal. Always start conservatively then gradually increase the length and the angle or height of the stretch, then the number of repetitions. Stretching after exercise reduces the risk of injury and promotes recovery by counteracting stiffness and over-contraction after exercise. A good stretching routine can also improve heart rate recovery, muscle waste product removal, and lactic acid levels.

Food and water

During recovery, horses need to be allowed to drink and have access to electrolytes to rehydrate as soon as they finish exercise. Allowing them to drink even if they are hot and breathing hard doesn’t increase the risk of colic or laminitis. On the other hand, dehydration slows the clearance of mucus from the airways, can exacerbate conditions such as equine asthma, and when combined with dry feed can increase the risk of an impaction colic or choke.

Because sodium is needed to move water into the cells, providing water alone to a horse with electrolyte imbalances will only further dehydrate them. However, adding salt to drinking water should be done sensibly and with great care. Trials have found that horses have an abrupt 15-50% reduction in water intake the first day high sodium water is given. Do not exceed 30g of salt per 5 litres of water and always provide separate plain water.

There are plenty of other electrolytes (potassium and chloride) in roughage, and lucerne is high in calcium. Extra magnesium may be needed. Soaked hay can also increase water intake, but a mineral supplement and extra salt must be added. Large quantities of electrolytes are lost in the process of soaking, but are retained in steamed hay. Rehydration also improves appetite and digestion, and refuelling the muscles requires water and electrolytes. The muscles also require nutrients that support the anti-oxidant defence system, and amino acids to repair and rebuild muscle tissue.

To optimise recovery once heart rate, body temperature and breathing have settled, it’s important that horses have unlimited access to forage. The digestive system is exposed to increased heat during exercise. Combined with the redistribution of blood flow away from the gut to the muscles and skin (especially during hot/humid conditions), the gut biome and digestive function can be compromised during recovery. Forage, beet pulp, and soymeal are excellent prebiotics, and support digestive function.

After exercise, swelling of the fetlock area is common. Also known as ‘stocking-up’ it is more common in confined than paddocked horses. Walking is important as lack of physical activity after exercise delays recovery. There are many ways to assist recovery of the lower legs. Hosing with cold water or a spa for 10–20 minutes two to three times a day, and ice boots, wraps or placing the limb in a bucket of ice water for 20-30 minutes two to three times daily, help reduce inflammation and pain.

Correctly applied wraps and bandages exert gentle compression promoting movement of excess fluid from the soft tissues back into the lymphatic system and bloodstream. Ensure the leg is not wrapped too tightly and check the response after a couple of hours. Sweat bandages and poultices (applied over several days, 12 hours on/12 hours off) often include DMSO, Vaseline, mineral oil, Epsom salts, bentonite and glycerine, and help to reduce swelling.

Sometimes overlooked in recovery is undisturbed rest, especially after travelling, intense exercise (cross country in a three-day competition), or after each day in multi-day competitions. Horses can only achieve proper sleep when lying down. They are able to sleep standing up due to the specialised stay apparatus in their legs, but they only enter deep REM sleep when lying down with their head on the ground.

In horses, sleep occurs in cycles or episodes of five minutes light sleep followed by five minutes of deep REM, then five minutes more of slow wave sleep. The usual sleep pattern for horses takes three to five hours per day, mostly between midnight and 5:00am. Adult horses can’t maintain longer than 15 minutes in full lateral recumbency because the weight of the abdominal contents compromises respiration.

During exercise there are intricate processes and changes occurring throughout the body systems. As a general rule, the harder/more intense and/or longer the exercise, the longer the recovery period needed. Inadequate recovery leads to stress, and health and behavioural changes. Understanding how to support recovery is an integral part of training, riding and competing.

Dr Jennifer Stewart BVSc BSc PhD is an equine veterinarian, CEO of Jenquine and a consultant nutritionist in Equine Clinical Nutrition.

All content provided in this article is for general use and information only and does not constitute advice or a veterinary opinion. It is not intended as specific medical advice or opinion and should not be relied on in place of consultation with your equine veterinarian.