Protecting future soundness

Musculoskeletal disorders end the careers of many equine athletes, but the problem may have its cause in the early months of life, writes DR JENNIFER STEWART.

The career of many equine athletes can be relatively short – two to three years for a racehorse and three to four years for eventing, show jumping and dressage horses – with musculoskeletal disorders a major cause.

A skeletal disorder that develops in growing foals and is a common cause of pain and lameness for adult sporthorses is developmental orthopedic disease (DOD), which affects 10-65% of all weanlings. The term DOD was coined in 1986 by the American Quarter Horse Association to describe skeletal problems in growing horses: limb deformities, bone cysts, contracted tendons, club feet, joint enlargements, wobblers, osteochondritis dessicans (OCD) and physitis, a condition causing deformities in the legs of young foals.

DOD is caused by disruption to skeletal development. Anything that disrupts the blood supply, or conversion of cartilage to bone, creates pockets of dead tissue that can detach and lead to structurally compromised bone, and bone/cartilage chips or fragments in joints. It occurs worldwide and is more common in Thoroughbreds, Standardbreds, Quarter Horses and Warmbloods. The diagnosis of DOD can be life-changing, and because each of the body’s tissues has a defined period of growth, weaning requires special vigilance.

Maximum bone growth occurs from three months before birth to around nine months old and muscle from two until twenty-two months old. Muscle growth should not be pushed forward while the bones and joints are vulnerable. A lighter, leaner weanling with appropriate height (height is an indication of bone growth) is the ideal. For foals with a genetic potential for rapid growth, correct dietary management helps to regulate that growth and prevent excess condition.

The period from three months before birth to five months old is one of turbulent change for the musculoskeletal system. Many remodelling processes (that profoundly influence the strength and integrity of bones and joints) take place. From five to eleven months, growth and development slow. Because these processes are only active during the first year of life, DOD lesions only develop during this period – even though they may not show up for months or years.

Most lesions are not detectable (even with x-rays) until the damage causes lameness or joint swelling. DOD is present long before signs appear and specific joints have precise windows of vulnerability. Hock DOD is usually present at one month of age, although signs may not show until the horse is six months to three years old. Stifle lesions develop between three and eight months, but may not be apparent until two years of age, and shoulder OCD or bone cysts may not be evident until twelve to eighteen months old.

During periods of vulnerability the joint is susceptible to the combined effects of nutritional imbalances, hormones (insulin and thyroid), body weight and growth rate. Management will determine whether the normal variations in cartilage thickness resolve, or progress to DOD. Although osteochondrosis lesions are likely to happen during the first few months of life, the period of growth between six months and one year can be significant in correcting DOD through diet and feeding changes that encourage consistent, slow growth, offering us an opportunity to guide and regulate growth and protect future soundness.

Key factors identified in the development of DOD are genetics (25%), biomechanical stress, rapid growth, diet and hormonal influences (75%). Biomechanical stress is affected by body weight and exercise, with excessive loading disrupting cartilage blood supply. Foals who show signs of hock and stifle OCDs as yearlings tend to be heavier at birth and weaning, and grow rapidly from three to eight months. Hock DOD occurs more frequently in foals born taller and heavier; those that grow faster in height/weight and are 5kg or more above average at four weeks of age and 14kg plus at eight months.

Foals who are intermittently upright in the pasterns also have more frequent and severe lesions. Taller foals, or being 5.5kg heavier at 25 days and 17kg at 120 days, or faster weight gains from three to five months, increase the chance of stifle and/or shoulder lesions. Wobblers often have a heavier body weight; taller wither and hip height from birth to 12 months; and faster weight gain at one to two months, four to five months and seven to eight months.

Exercise is another factor because muscle and bone are moulded by the amount and character of exercise. Weanlings with free access to pasture have stronger, healthier musculoskeletal systems compared to young horses confined to box rest, or box rest with short intense bouts of exercise. With free pasture access, foals gallop within a few hours of birth. When less than a week old, they can cover 10km/day and gallop for about 3.5 minutes a day in approximately 40 sprints. Confinement has a dramatic effect on daily exercise; a horse in a six-meter square yard will move only 1 km/day.

Additionally, there’s a connection between OCD and insulin levels after feeding. In foals three to twelve months old, the most common age for developing OCD lesions, sweet feeds and high sugar/starch feeds can cause high blood glucose and insulin and low blood pH for up to four hours. Swings in blood glucose and insulin have been linked with OCD in young horses, who have a more severe response when under 14 months old. DOD lesions are formed in a very limited period of time and changes can occur within three weeks on starch/sugar/grain-based feeds. Extruded and micronised feeds must be used with caution as their increased digestibility can produce more rapid and profound effects on blood glucose and insulin.

Magnesium deficiency has also been linked to DOD in growing horses. A recent study found supplementing foals with magnesium from birth to 12 months resulted in a 50% reduction in OC of the hock and fetlock at five months old, and a 14% reduction in stifle OC at 12 months old.

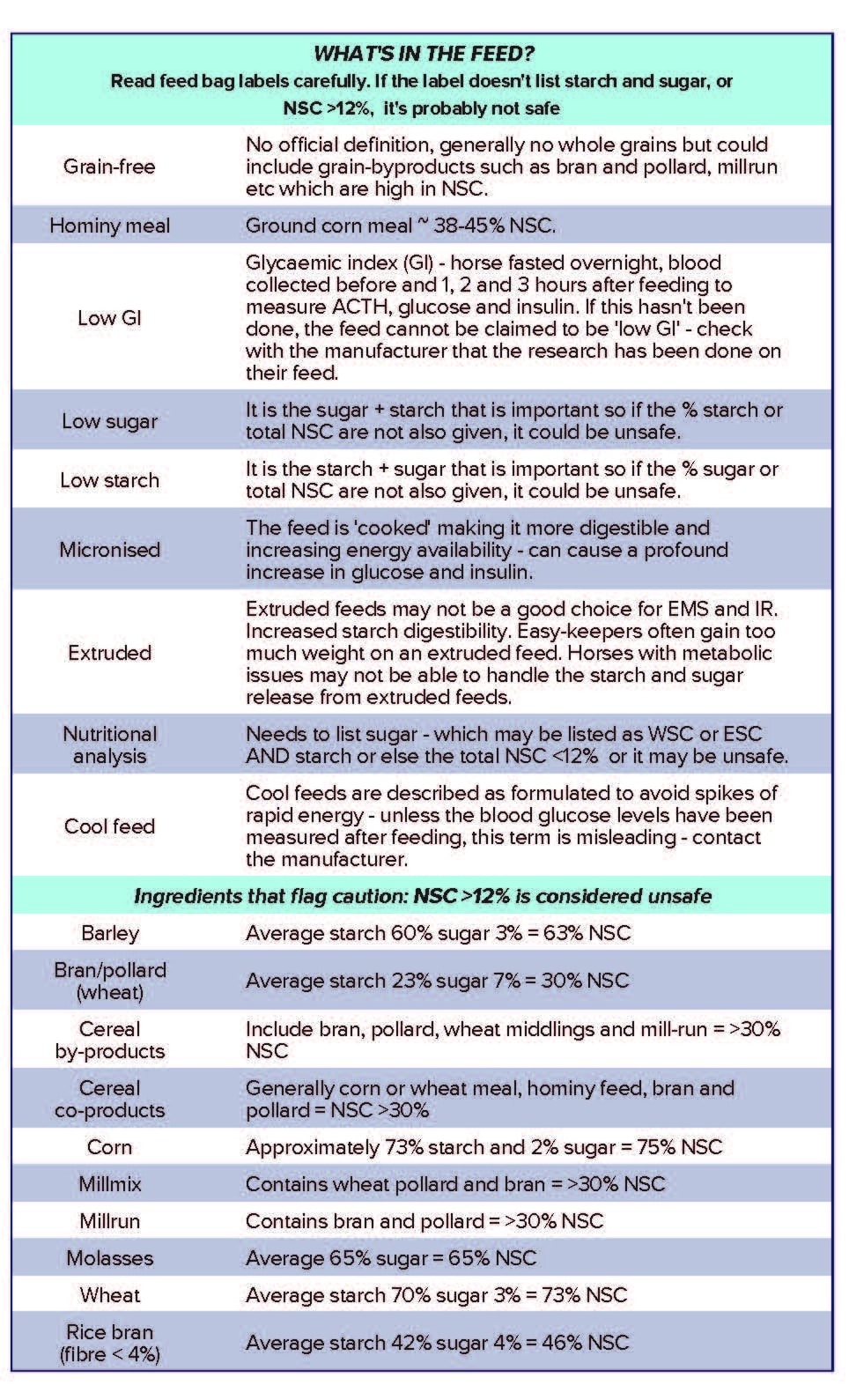

Avoiding feeds with >12% starch + sugar (=NSC) and providing a high fibre diet, linseed oil and a correctly formulated vitamin/mineral/amino acid supplement are the guiding principles. It’s worth becoming familiar with several terms commonly used in nutrition information and taking the time to read feed bag labels using the information in the table.

Because the window of opportunity for sound bone and joint development is only open for a short time, correct nutrition for young horses is essential and prevention must be a priority if future soundness is to be protected.

Dr Jennifer Stewart BVSc BSc PhD is an equine veterinarian, CEO of Jenquine and a consultant nutritionist in Equine Clinical Nutrition.

All content provided in this article is for general use and information only and does not constitute advice or a veterinary opinion. It is not intended as specific medical advice or opinion and should not be relied on in place of consultation with your equine veterinarian.