The latest research into laminitis has produced some interesting findings. Veterinarian DR. DOUG ENGLISH explains why laminitis is a more complex problem then was at first thought.

Equine laminitis (sometimes known as founder) is a complex, multifactorial syndrome that manifests as pain and lameness in the feet.

The modern horse is bigger and heavier than its ancestor, the Prewejski horse, which stood at around 14.2hh. However, hoof size has changed little over the millennia and the structure of the equine hoof today is very close to its mechanical limits, and has become a major focus for problems.

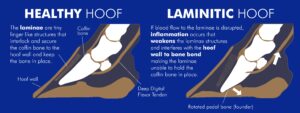

Essentially, laminitis is caused by a cascade of inflammatory and vascular reactions, which cause damage to the structure and function of the hoof’s suspensory apparatus: the lamellae attaching the distal phalanx (the last bone in the hoof) to the hoof wall. Such damage can be irreversible or take years to correct. When the horse stands, weight bears down on the attaching structure causing further problems. The ideal fix is 100 per cent no weight-bearing on hooves, which is, of course, unachievable as horses cannot lie flat for more than an hour or two.

And before we go further, it may be useful to note that a disease and a syndrome are not one and the same: a disease has a definite cause with distinguishing symptoms, while a syndrome is a group of symptoms that might not always have a definite cause.

Symptoms indicating laminitis

There are a number of symptoms that suggest laminitis:

· Presents as lame

· Reluctant to move

· Leans backwards to even up weight distribution, which is mostly on the front feet of a normal horse

· Sensitive when a hoof tester is applied to the toe

· Gross hoof wall abnormalities with a wide or divergent white line

· A flat sole

· Diverging rings

Laminitis is now considered to be a clinical syndrome associated with systemic diseases such as endocrine disease, sepsis, or systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), rather than being a discrete disease entity.

In fact, the understanding of laminitis as a primary and severe disease of the basement membrane (the membrane providing cell and tissue support) in the hoof, now needs to be revised. Current data indicates that before symptoms become evident, a variable phase associated with gross changes in the hoof capsule, along with stretching and elongation of the lamellar cells, are an early and key event in the onset of the disease.

Laminitis associated with endocrine disease is now believed to be the predominant form in horses presenting with lameness. Their insulin levels are several times higher, they have higher plasma triglycerides, and higher body condition scores (in other words, they’re fat!).

Insulin dysregulation

Many of these cases are, but not necessarily, older horses with either PPID (Pituitary Pars Intermedia Dysfunction or Equine Cushing’s) where the adrenal glands produce excess cortisone, or EMS (Equine Metabolic Syndrome) in which fat cells produce a hormone that elevates cortisone levels, altering the normal insulin response and producing high levels of insulin and elevated blood glucose.

PPID is a disease of the pituitary gland caused by degeneration of the hypothalamus, a part of the brain that plays a vital role in controlling many bodily functions. This degeneration sets off an unwelcome chain reaction: it limits production of the neurotransmitter dopamine, which controls and limits the production of ACTH (Adrenocorticotrophic hormone) in the middle part of the pituitary gland, which then in turn is over secreted and stimulates excess cortisones from the adrenal cortex.

It’s the excess cortisone and resultant insulin dysregulation in horses with either PPID or EMS that puts them at a higher risk of developing laminitis. Fortunately, PPID can be treated with the drug pergolide, known in the marketplace as Prascend, a dopamine agonist (the opposite of an antagonist) which stimulates the production of the dopamine necessary for restoring balance.

Risk factors

A 2019 survey identified a number of risk factors associated with laminitis:

· Lack of regular daily exercise: standing in small areas is not conducive to good hoof health. Historically, horses are athletes that moved in herds over wide areas, and they still need to continually move for good health.

· Serious illness such as intestinal infection following major abdominal surgery

· Obesity

· Lack of exercise

· Genetic predisposition

· Previous history of laminitis

· High levels of cortisone from different causes

· Hoof care intervals greater than eight weeks

· Soreness following routine hoof care

· Seasonal increases in grass fructan: a major cause of laminitis is linked to seasonal increases in the concentration of grass fructans (chains of fructose molecules). Fructose is the monosaccharide sugar common in fruit, and the main sugar in honey. Most mammalian biochemistry cannot handle it in large amounts.

Laminitis and grazing grass

The relationship between laminitis and grazing grass is complex, however a number of causal factors have been identified and should be kept in mind:

· Access to pasture later in the day when photosynthesis from the sun has boosted its sugar content. Susceptible horses should be removed from the paddock before 11:00am, and not be put out until just before dawn.

· Spending only short periods on grass educates the horse to eat too fast.

· Use of grazing muzzles part time: this causes compensatory eating and the ingestion of substantial amounts of non-structural carbohydrates in a short period. Use a muzzle all of the time or not at all. (See this issue’s Ask an Expert for more on non-structural carbohydrates).

· Feeding ryegrass in pasture or hay.

· Avoid grazing susceptible horses where the grass is short – it has increased sugar.

· Fructans like oligofructose increase during periods when grass can photosynthesise but can’t grow e.g. cold weather, water logging, drought.

· Fructans are reduced by topping or cutting grass because the plant’s fructan stores are then used to produce new leaves.

· Fructans tend to be highest at the start and the end of the growing season, particularly in regions with shorter growing seasons.

· Polymerisation is the process in which small molecules combine to form chains. Fructans with lower degrees of polymerisation (DP) are likely to be more rapidly broken down than those with higher DPs. DP varies between species, from brome grass which has 26 DP fructans (26 fructose units) up to 260 DP fructans (260 fructose units) in Timothy. Fructans cannot be broken down by enzymes in the small intestine and are fermented by micro-organisms in the large intestine creating volatile fatty acids and lactate, with the potential for large amounts to cause acidosis resulting in laminitis. The higher the DP, the greater the danger of laminitis.

Don’t miss our November/December issue, in which Dr Doug takes an expert look at mycotoxins and their implications for laminitis.