The Wilson sisters are famous around the world for their equestrian achievements. Candida Baker spoke to Vicki Wilson just as she was about to leave the North Island for the U.S to defend her Road to the Horse Colt Starting Championship title for the third year in a row.

Riding on the sheep’s back. It’s an expression usually associated with Australia’s wool industry but for one of New Zealand’s top equestrians, Vicki Wilson, it was literally the start of her unusual and stellar career.

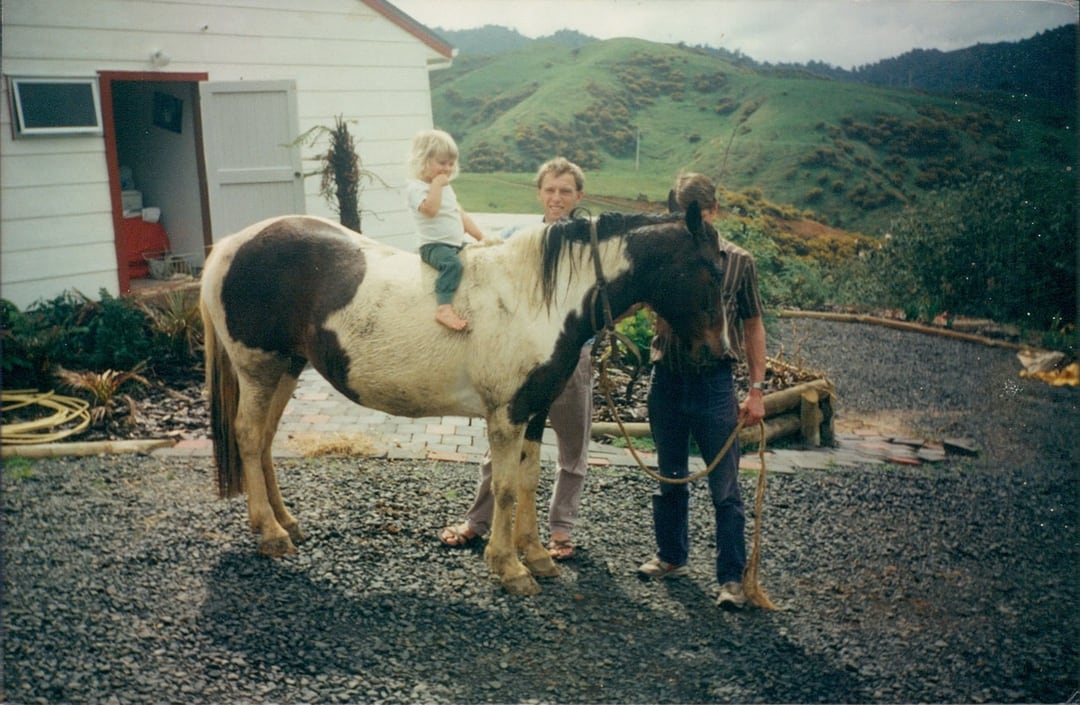

I didn’t get my first pony until I was two-and-a-bit, she tells me on the phone from her home in Hawke’s Bay as if waiting that long was a tough slog for a toddler. But for this toddler, it obviously was, so Vicki did the next best thing.

Until I was two I just used to climb on the pet sheep that were in the paddock next to our house, and cling on until I fell off.

She still remembers climbing through the fence into the paddock beyond and trying to clamber up on sheep that were, in her words, a bit wild. No wonder her parents bought her a pony.

Vicki, 26, and her two sisters, Kelly, 31, and Amanda, 28, are famous, not only in New Zealand but world-wide, not just for their derring-do in the showjumping ring, and for Vicki’s extraordinary performances in the US Road to the Horse Colt Starting Championship, in which she’s been the only woman to win it twice in a row, but also for their work with New Zealand’s wild horses, the Kaimanawa, to avoid them having to be culled when the herd exceeds sustainable management numbers. Their journey with the Kaimanawa produced a book (written by Kelly), and a documentary series, Keeping up with the Kaimanawas, (produced by Amanda).

In 2015, the Wilson sisters spent 100 days taming 11 wild American mustangs in the West, which has been documented in a book and documentary called Mustang Ride.

But if Vicki’s life, in which she’s blended all our passions into her breeding, starting and rehabilitation establishment at Hawke’s Bay, seems luxurious now, it wasn’t always like that growing up on their parent’s farm in the Waikato region of the North Island.

My parents weren’t wealthy, she says, and although they encouraged us to ride, we could never afford a good or educated horse, only the dangerous and problem horses that were other people’s rejects. But we were all desperate to ride so we took them on.

Although her parents were supportive, her father had broken his back in his twenties, and no longer rode, and her mother, who had learned to ride as a teenager, was an occasional rider, says Vicki. But realising they had three horse-obsessed daughters, they supported them as best they could. Growing up in a Christian household encouraged them to dig deep whenever a problem came up, and it’s a solution-based approach to horses which has served Vicki and the thousands of horses and riders who have come to her for help one could say almost miraculously well.

All my first show jumping horses were other people’s rejects, she says. What it fired in me was a curiosity as to whythis horse wasn’t performing. I learned to go through an entire process with a horse and to gradually eliminate all the possible physical problems foot balance, saddle fit, dental problems, incorrect feed for that horse. Looking back with the knowledge I have now there were even more horses I could have fixed, but I was learning as I went.

Vicki’s learning took her to extraordinary places. After working her way up from local gymkhanas, she’s now won more awards at the New Zealand Horse of the Year show than any other rider in history. Winning the World Cup in 2014 took her show jumping career to another level, and she has also competed under the New Zealand flag in Europe with many wins and placings. She’s performed all over New Zealand and Australia in bridle-free, bareback stunts, jumping to 1.82m bareback and 1.95 in a saddle in Puissance events.

In 2018 Vicki defended her title in the US competing against two former Road to the Horse champions, this time starting two colts instead of one at the same time. It’s almost too much to contemplate that in this one discipline alone Vicki nailed the following firsts, by being the first rider from the English discipline to compete in Road to the Horse; the first rider from the English discipline to win Road to the Horse; the first New Zealander to compete in and win the Road to the Horse; the first rider to jump bareback in the Freestyle event; the first rider to wear a helmet; the first rider to use an English saddle and, in a testament to her own work, the first rider to do body work on their colt.

I was already in awe of this woman I’d seen last year at Equitana changing several young women’s relationship with their horses and the way the horses used their bodies right in front of my eyes, but by the time I digest all this, I feel in need of a nice cup of tea and a lie down. How one earth, I wonder, does she do it?

She laughs. I don’t know, it just grew and unfolded as it went, and I’m on a journey which is leading me to inspire and educate people around the world so they have a better relationship with their horse. That’s what keeps me going. Also, I think if you don’t love what you’re doing, and you don’t wake up every morning ready to jump out of bed and do that thing , then why do it?

That thing has also led her to take over all the shoeing and trimming of the 100 or so horses she has on her property. I took over the shoeing about ten years ago, she says. To me foot balance is perhaps the most fundamentally important element of all, and I wanted to be sure that it was correct for all my horses, and for my clients, so I decided to do it myself ¦it keeps me busy, she concludes, in what is possibly the understatement of the year so far.

Her equine body therapy work REMOVED WHICH has become core to her life with horses came about when she was mentored by a well-known New Zealand equine body therapist Dan Erikson for six years.

How I’ve learned is that I ask questions. I’ve watched every horse trainer I’ve ever met, every equine therapist, every vet, dentist and farrier, and I’ve asked questions why are you doing this? What’s this for? What will the result of this be? she says. Most importantly the horse has been the teacher. Sometimes of course, horses with behavioural issues will turn out to have kissing spine, or arthritis, or a bone spur – something that has to be managed rather than cured, but it’s still about giving them quality of life. I don’t feel I need to study under any one particular person, or that there is any one method that

works we have to be open-minded and not afraid to continue exploring. To me, every single horse is different and every horse requires a different program to help it fulfil its potential.

One of Vicki’s many tools is the use of the Equisystem, a bandage that is wrapped around the horse to help horses engage their hindquarters. It’s a technique she’s refined from her time show jumping in Europe 12 years ago.

I saw that almost all the trainers used a leather strap going over the horse’s rump and loins, she says, and what it creates is these very uphill, powerful horses, so I decided that when I got home I would try it with my horses. Well, it was a bit of a disaster they were bucking, and kicking, and clearly not happy, so I thought how do I change that? Vicki’s solution was to use the elastic bandage. I’ve refined the bandage quite a few times over the years, she says. We’re not wanting to hurt or restrict the horse in any way whatsoever, all I want to do is to remind their brains that they have a powerful engine behind.

At Equitana, three of Vicki’s hand-picked young women and their horses were helped with the bandages, and to be honest, if I hadn’t seen it with my own eyes I would never have thought that it could make so much difference (in conjunction, of course, with the instantaneous body work Vicki does during a lesson).

The thing with horses is that they are actually naturally heavy on the forehand, Vicki explains. They have a heavy head, neck and shoulders, and they tend to work forward in their natural state they carry 60% of their weight on the forehand and 40% on the back. Add a 70-95kg rider to that, and suddenly 80% of their weight is on the forehand. It’s our job to make sure that they can correctly use their body to support a rider. The bandage is a reminder that they have an engine to help them push from the end, so they can lift through their core, and take contact forward. This pays dividends in all work, not just jumping, because it’s vital that horse should be on the bit through its body, not through its neck, which is what we tend to see far too much of.

Horse welfare is paramount to all three sisters, and is one reason why they became involved with the Kaimanawa program which has seen the numbers of wild horses gradually culled over the years to bring the herd down from over a 1000 to 350, which the Kaimanawa Heritage Society believes is a sustainable amount on the million wild acres they have to live in.

One of the Kaimanawa ponies that came from amuster went on to win New Zealand’s prestigious Pony of the Year award, she says. When we first got involved with the re-training program, any horse over four was going to slaughter, and after I’d seen these beautiful, strong horses in their home ranges, my sisters and I agreed that there was no reason for any of them to be slaughtered.

The first time they took Kaimanawas home, 11 horses, of all ages and genders were lucky enough to find themselves with Vicki.

Within 45 days we had an 18-year-old stallion cantering down the beach safely with a rider on, she says. She feels deeply for the horses, who, contrary to the US where mustangs are held in custody for six months to two years before being rehomed, or Australia where brumbies are given some time in holding yards, are mustered by helicopter into stockyards, and the very next day are delivered to their new homes. I do believe the musters are done as quietly and gently as possible, she says, but the fact is that we are taking these wild horses out of the ranges and putting them into prison cells. So it’s essential that you get the rope on them and start walking them off your property as soon as possible, because freedom is so important to them.

The rehoming program has been working so well that in that last four musters no horses have gone to slaughter. It’s pretty incredible for such a small country that we’re managing our wild horses so well, she says. But it’s also a case of trying to create easy transitions a two-year-old will transition into a human way of life much easier than an older horse.

For Vicki these problems are simply another way to learn solutions. What I’ve learned is to feel, to observe, to listen and to have empathy, she says. Wild horses senses are much more acute than a domesticated horse, but, on the other hand they are also much more family oriented than the average domesticated horse, because their family is all important. I think that’s why they become such loyal, brave friends. You become their family. They become yours.

For Vicki working with wild horses is all about the feel, timing and pressure. I’m not saying that people should get cross at their horses but unfortunately it happens, she says, however, you can be cross at a domestic horse and the next day they ll forgive the person, but if you put a fraction too much pressure on at the wrong time, the wild horse won’t forget in a hurry. There are no shortcuts training wild horses. But if you do it right, and learn what you become is a horseman or horsewoman, rather than just a rider, and to me that is much more important.

The idea of naughty horses is something that distresses her. No horse, in my opinion, wakes up saying Oh today I want to be naughty, and be smacked and punished, she says firmly. What I’ve discovered is that the horse that doesn’t, or can’t do something we’ve asked for has a problem, and it’s our job as its rider, or trainer, or owner to find out the problem and offer a solution.

If winning the Road to the Horse was tough in 2017 against all women competitors, tougher again in 2018 against two previous winners, and with two colts to start, it’s going to be tougher again in 2019 with Vicki going head to head with previous winner and multiple colt starter Nick Dowers. Nick, the 2016 World Champion and National Reined Cow Horse Futurity Champion, will be meeting the New Zealand showjumper and two-time Road to the Horse Champion head on with three horses to start simultaneously in the round pen. Vicki doesn’t intend to try out the technique beforehand. We ll just turn up on the day and see what happens, she says mildly, as if starting three startled colts in one round-pen will be a walk in the park.

2017 was pretty tough for me because I dislocated my shoulder on the first day, and I was in agony, she says. I had to change my approach. One of the things I did that I was really happy with was to teach my horse to lead really well, because I couldn’t risk my shoulder being pulled. It stood us both in good stead by the end of the competition, because he was so bonded with me. That horse, Kentucky, came home to New Zealand with her and has since gone onto to become a wonderfully successful all-round horse.

Vicki’s goal is to educate people around the world to be the world’s best teacher they can be for their horse. Personally for me, it’s vital to have healthy, happy horses, she says. Even my top showjumpers round up stock, swim in the river, get ridden on the beach, have time off, do groundwork. Every horse needs variety, just as we do in our lives, and every horse deserves to be working at its physical peak. Whatever that is for that particular horse.

She’s off again in just a few days to compete in the US Road to the Horse once more and see if she can make it a hat trick of wins. Beyond that she has plenty of other goals. I love my breeding programme, she says, and I want to bring on my young horses to have long, healthy, happy competition careers. I’d love to compete in the Longines World Champions Tour, but even more importantly I want do as many clinics and workshops around the world so I can continue to teach people about their horses bodies.

Her life, she admits, used to be about winning. It’s not anymore, she says. I have a partner, Michael (Whittacker), and he works with me with the horses. I compete once a month rather than once a week, and what I want now is for every horse that comes through my place to be set up to have a long career.I can’t help thinking that it’s not just the horses that are going to have a long career, and that Nick Dowers may have his work cut out.

Article taken from HorseVibes, March 2019.