Is it ‘The Virus’?

Horses can be infected by a number of viruses and if your horse is unwell, it’s a mistake to take it lightly. DR JENNIFER STEWART offers her expert advice.

Does your horse cough during or after exercise? Do they have a nasal discharge? Or are they performing below the level you expect from them? If so, they may have a respiratory disease. Perhaps it’s ‘The Virus’ – but if so, which one?

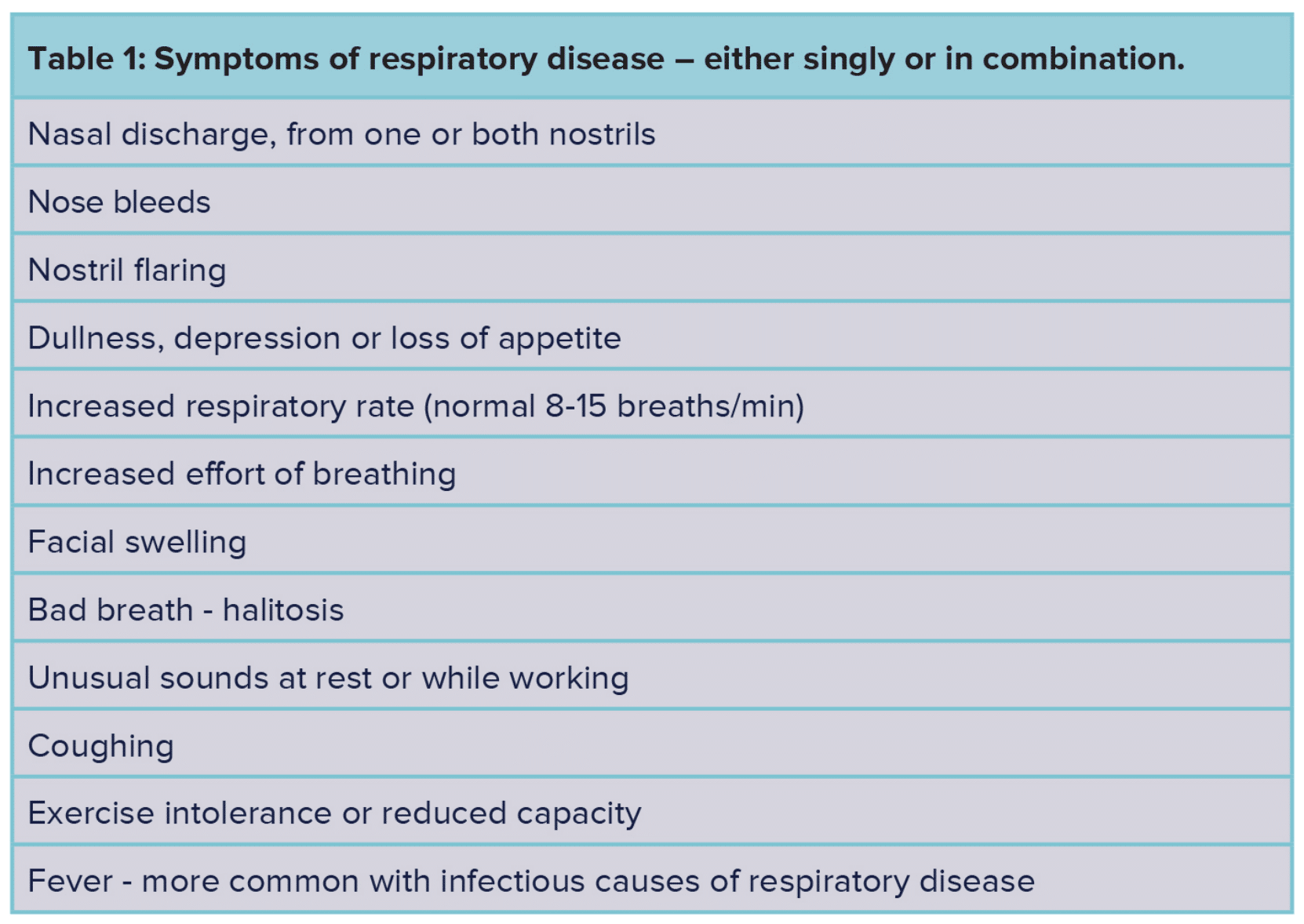

As the temperature drops and we move into winter, our horses may experience health conditions related to the change in season, one of the most common of which is respiratory disease. There are many symptoms of respiratory disorders (Table 1) and as many causes, including infectious agents (bacteria, viruses or fungal spores), inflammation due to exposure to dust or other toxins in the air, and parasites. Bacteria often take hold in young, stressed or immune compromised horses, and viral infections can cause disease and create conditions for a secondary bacterial infection.

Respiratory issues can be infectious or non-infectious, but they can be interrelated, coexist, and combine to increase the risk, occurrence and severity of disease. Equine asthma is the major non-infectious respiratory disease of the lower airways. Triggered by inhaled environmental allergens such as dust and fungal spores, which irritate the airways, it results in hypersensitivity, constriction and mucus secretion. It is usually a chronic disease with a slow onset, but acute episodes do occur. Also known as RAO (Recurrent Airway Obstruction), COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease) or IAD (Inflammatory Airway Disease), 25 to 80 per cent of stabled horses suffer from equine asthma to some degree.

Herpes virus

World-wide, at least 58 viruses are known to infect horses. The common respiratory viruses include equine herpesvirus-1 and herpesvirus-4 (EHV -1 and -4), equine influenza virus (EI), equine arteritis virus (EAV) and adenovirus. In Australia, the common viruses are EHV-1, EHV-4 and equine rhinitis virus (ERV). Once infected, the herpes virus remains with the horse for ever. When stressed or suffering a respiratory infection, symptoms of herpes may reappear or the horse may remain symptom-free but shed the virus, thus exposing other horses. A horse can be infected with multiple herpesvirus species, which can result in immunosuppression and increased susceptibility to new or reactivated infections. Reactivation and shedding of EHV is often associated with transport and travel and can continue for over two weeks after a journey. Furthermore, concurrent EHV infections play a role in reactivation of latent infections, predisposing foals to the potentially fatal ‘rattles’ infection with Rhodococcus equi bacteria.

Herpesviruses generally cause a mild nasal discharge. However, in foals and aged horses herpes can produce a flu-like illness with fever and cough, neurological disease (mild incoordination, loss of bladder and tail control, skin desensitisation around the vulval area), and abortion. Over 85% of horses test positive to exposure to herpes. Due to the risk of abortion, as well as illness and death in young foals, it’s particularly problematic for stud farms, which may choose to make vaccination mandatory for visiting mares.

Hendra and strangles

Another cause of respiratory and neurological disease is Hendra virus. Since it was first identified in 1994, there have been over 100 confirmed or probable equine cases, all of which died or were euthanised, and seven known cases of Hendra virus infection in humans, four of which were fatal. Hendra is challenging to diagnose in the field as the signs are non-specific: a fever, lethargy and depression. The progression to respiratory and neurological disease is usually rapid and may result in watery or frothy, blood-tinged or brown, nasal and/or oral discharge.

Strangles, another cause of infectious respiratory disease, produces a thick, yellowish discharge. Caused by the Streptococcus equi bacteria, strangles in highly contagious and spread by discharge from the nostrils or pus from burst abscesses. Signs include depression, fever and loss of appetite. Veterinary monitoring is helpful as at least 10% of horses infected with strangles will end up with chronic infections in their guttural pouches. Horses can carry bacteria in the pouch for months after they have recovered, and although they appear clinically well and healthy with no signs of infection, they shed bacteria in nasal discharges and are a source of infection for other susceptible horses.

Zoonotic pathogen

In foals, a discharge from both nostrils is common with infections acquired before, during or soon after birth: meconium aspiration; a herpes virus infection; or with rattles or pneumonia in older foals. Recently on some studs in Australia and overseas, Chlamydia psittaci, a zoonotic pathogen carried by birds, has caused pneumonia in vets, horses and farmers; a serous nasal discharge in adult horses; premature birth and abortions in mares, and acute respiratory distress with nasal discharge in new-born foals. Biosecurity and personal protective equipment is needed when dealing with Chlamydia-associated respiratory disease.

Several gastrointestinal parasites can also be a problem in foals and young horses. Roundworms (ascarids) are a danger to horses from two months to four years old – partly due to increasing resistance to common wormers. The larvae of roundworms migrate through the lung tissue and occupy the airways, causing a nasal discharge which may contain worms. Once lung tissue is damaged by the roundworms, viral or bacterial infections can occur. Threadworms (strongyloides) can also cause respiratory signs and a nasal discharge when they enter through the skin and migrate to the lungs. Horses paddocked with donkeys can become infested with a lungworm (dictyocaulus), which spends its adult life in the lungs, laying eggs that are coughed up, swallowed, and then passed in the manure.

Meet the virus

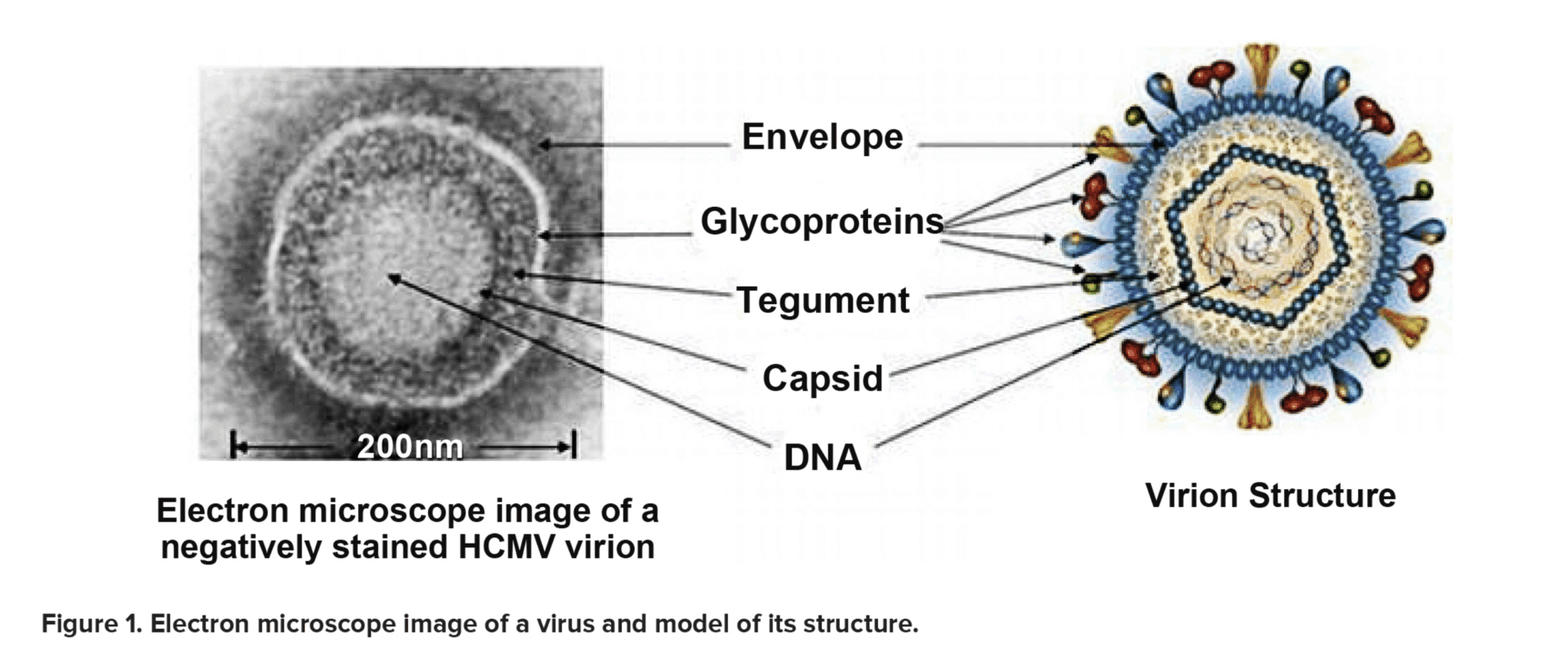

Viruses remain the most important cause of serious respiratory disease in adult horses and foals worldwide. Fundamental players in the history of life, their own ancient evolutionary history has remained largely unchanged over billions of years. The best estimate of the number of virus particles on earth today is close to 1031 i.e. 10 x 10 31 times. The smallest of all microbes (it would take 500 million rhinoviruses, the cause of the human common cold to cover the head of a pin) viruses can only exist by hijacking the cellular machinery of another living thing in order to reproduce.

Viruses cannot replicate on their own. They bind to the host cell and merge with the cell wall. Once they’ve invaded the host cell a steeplechase begins as they quickly shed their outer coat, bare their genes, inject their DNA and hijack the cell to reproduce viral DNA (Figure 1), ultimately exploding out of the cell in the form of new virions (virus particles) that infect other cells as they invade the body. During a viral infection there can be several million virions in every millilitre of blood.

The body’s cells are able to use antibodies to detect and destroy viruses. They bind to the virus like a lock and key, marking them as invaders. Each antibody producing cell can produce 2,000 antibody molecules per second, and within seven days, antibodies are detectable in the blood.

Vaccinations

Vaccinations combined with sound biosecurity practices can lower the risk of viral infections. Vaccination is a process by which we stimulate the immune system to produce a defence mechanism against selected diseases. In Australia, we can vaccinate our horses against tetanus, strangles, EHV, salmonella, rotovirus, and Hendra. Most of these vaccines are given depending on a risk assessment of the horse and may apply to breeding horses specifically. There is no standard vaccination program for horses, instead they should be designed after considering all risk factors and regulations. Directives regarding vaccination status may apply to horses participating in competitions and it’s important to check the policies of both the organisation and the venue.

During the last decade, the emergence of Hendra virus and the incursion of equine influenza have heightened the value of horse biosecurity practices. Prevention is without a doubt the best defence and many steps can be taken to lower the risk of respiratory diseases. Vaccinating against common viruses should reduce the incidence of these pathogens in your herd. Without these viruses, secondary bacterial disease is also a lot less likely.

Quarantining new horses before introduction to the rest of the herd helps prevent the introduction of any unwanted pathogens to otherwise healthy horses. Keeping horses divided according to age group can also help as many pathogens can be passed to younger horses by older horses with better developed immunity. For horses with inflammatory airway disease resulting from allergies, ventilation is key to improving their health. Often these horses do better if turned out to pasture due to improvement in air quality and more time spent with their head down grazing, which helps with the expulsion of the dust, toxins and mucus in their airways.

We are lucky here in Australia compared to many other countries as EI is not present, but there are other contagious respiratory diseases. By applying basic biosecurity measures – avoiding potential contamination of feed, water and equipment; insect and animal disease vector control; good hygiene when handling horses; and isolation of sick horses from healthy ones – we can help reduce infection. It’s also advisable to keep horses new to a yard, or those returning from competition, separate/quarantined for a period of time.

Although no vaccination can guarantee 100% immunity – and owners should always monitor their horses for signs of disease – there are vaccinations for tetanus, viral respiratory disease and strangles, and your vet can advise you on what your horse should be vaccinated for and how often (vaccination programs will differ for individual horses and situations). However, in a stud situation a complete vaccination program for tetanus, strangles, EHV and salmonella is recommended.

While there are no guarantees, there are many things you can do to reduce the incidence of respiratory disease – including vaccination, biosecurity and air hygiene.

Immune system support

Vitamin E is abundant in fresh grass, but declines rapidly after cutting and baling to make hay. Horses with little or no grass have extremely low levels of vitamin E and along with selenium, these are two of the most important and often deficient nutrients. For an average horse (400-500kg) the basic vitamin E requirement is 1000iu/day and 2000iu for immune system support. Fresh grass is a rich source of omega-3 essential fatty acids, but these too are lost during cutting and baling. Linseed and chia seeds are excellent sources of omega-3 and the average horse will benefit from 100-200g/day or 125–250ml of linseed oil. There is no doubt that vitamin C is a central pillar in health and fresh grass is a rich source, but blood levels fall in winter on hay diets. Most mammals produce vitamin C from glucose, it can’t however, be stored in the body. There’s much we don’t know about vitamin C in horses and whether supply exceeds demand with age, injury, infection, musculoskeletal conditions or wounds. High doses (20g/day) can cause gut irritation and diarrhoea and extra caution is needed in horses with insulin resistance or iron overload. As a rule of thumb, 10grams/day can support the anti-oxidant defence system, but the diet must be balanced first.

Global travel

The resurgence of certain viruses is caused, among other things, by the growth of international equine movement for breeding and sport events, as well as an expansion in the geographic distribution of viral pathogens.

Winter outbreaks

The majority of viral outbreaks associated with respiratory disease in horses occur in winter. Dry, cold air affects the local defensive mechanisms of the airways and increases susceptibility to irritants and infective pathogens that gain entry via the respiratory tract. During winter months, horses are more likely to be indoors and due to dust, fungal spores, bacteria, endotoxins and viruses that horses can inhale, air quality in stables and barns is poorer than outside. Horses who are housed are also often in closer contact to other horses, and this can increase the spread of airborne pathogens. If you notice your horse begins to cough more when they are brought inside or when there is increased dust or other particles in the air, it may mean they have an inflammatory airway disease. If multiple horses are coughing it may be a sign that there is a virus circulating. Determining the cause requires a full veterinary clinical examination and often additional investigations.

Horses that are well and healthy may produce a small amount of clear, watery nasal discharge after exercise – that little trickle at the end of the ride or after a long trip in the trailer that goes away without a second thought. However, in the case of a suspected respiratory disease, a veterinary evaluation is advisable to determine the possible cause, and the appropriate treatment and management. The examination may include a nasopharyngeal swab; endoscopy; and guttural pouch, tracheal and lung washes. The treatment is usually a combination of management strategies and medications, depending on the cause of the respiratory disease and the infectious agent (if any) involved.

Most routine respiratory cases resolve with minimal treatment and no permanent damage. With others, it’s a mistake to take them lightly and timely veterinary intervention is needed for the best outcome.

Dr Jennifer Stewart BVSc BSc PhD is an equine veterinarian, a member of the Australian Veterinary Association and Equine Veterinarians Australia, CEO of Jenquine and a consultant nutritionist in Equine Clinical Nutrition.

All content provided in this article is for general use and information only and does not constitute advice or a veterinary opinion. It is not intended as specific medical advice or opinion and should not be relied on in place of consultation with your equine veterinarian.