Antimicrobial resistance

How big is the problem and what can be done to avoid it? DR SARAH GOUGH explains.

Although antimicrobial resistance is a commonly used term, its significance is perhaps less well understood. So, what is it? According to the World Health Organization, antimicrobial resistance occurs when bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites no longer respond to antimicrobial medicines. The implications of this become clear if we think back to the early 1900s, prior to the discovery of antibiotics, where the average life expectancy of humans was nearly 25 years less than it is today, and a simple wound infection, never mind a surgical procedure, could easily result in death.

So why are these microbes becoming resistant? In short, every time we use antimicrobials (most commonly antibiotics), we risk the development of genes that create antimicrobial resistance in the exposed microbes. Additionally, while it is normal for a microbe to have inherent resistance to one or more antimicrobial, the frequency of bacteria or fungi that are resistant to all available antibiotics and antifungals is increasing dramatically.

In response, we need to reduce our use of antimicrobials overall, and when needed, ensure they are prescribed appropriately. This process is known as antimicrobial stewardship, which should be at the forefront of our minds as we move into this era of antimicrobial resistance – a true ‘one health’ problem.

Antimicrobial resistance

Not all microbes are created equal, so different antibiotics and antifungals are selected to treat different bacteria or fungi. This is based on the spectrum of activity of the specific drug against a specific pathogen. Part of this decision is based on knowledge of the pathogens likely to be involved in each individual case, plus the site, cause, characteristics etc of the presumed infection as confirmed by laboratory testing. Some bacteria will have inherent resistance to certain types of antibiotics and the same is true for antifungals.

However, the primary concern with increasing antimicrobial resistance is the development of new resistance patterns in microbes that were previously susceptible. Every time your horse is prescribed an antimicrobial, your vet should be considering the following key details:

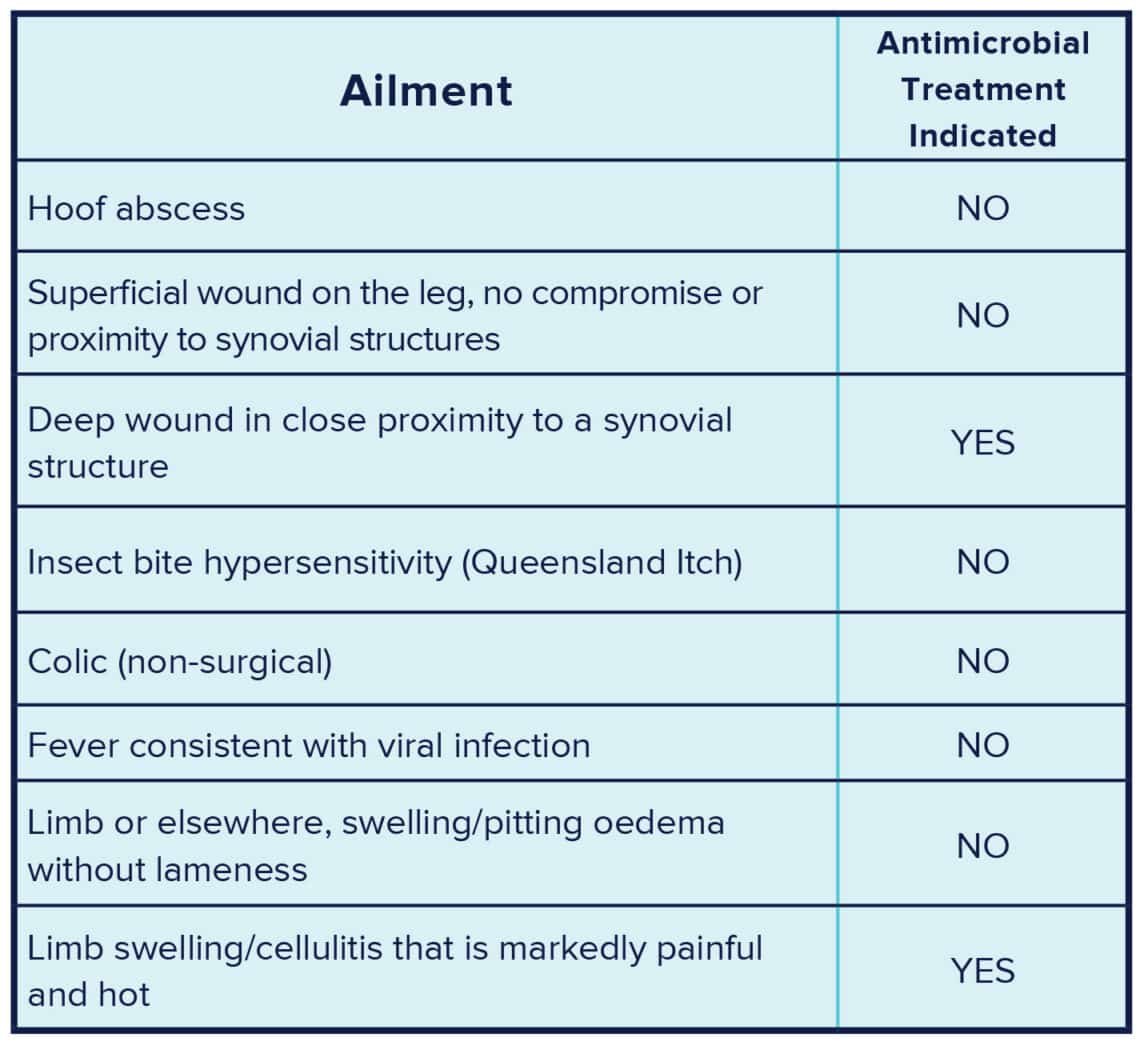

- Are antimicrobials warranted? Many conditions have historically been treated with antimicrobials ‘just in case’, when their use is neither indicated nor appropriate (see Table 1), and this needs to change.

- If antimicrobial treatment is warranted, then collection of a sample or swab for culture and bacterial susceptibility testing or microscopy is important so that antimicrobial selection can be guided.

- Selecting the most appropriate antimicrobial should be based on: use of first line antimicrobials (those not critically important to human health); the antimicrobial’s effectiveness against the bacteria or fungi most likely to be present; its appropriateness for the situation (for example, some antibiotics are ineffective in purulent material so shouldn’t be used for treating abscesses); and that an appropriate dose rate and frequency can be achieved.

The decision is not always straight forward, and in many instances deciding not to reach for antimicrobials is appropriate.

Fevers

Similar to the largely outdated practice of medical doctors prescribing antibiotics to patients with a cold, veterinarians have often administered antibiotics in cases of fever. The most common cause of fever and malaise in horses (in the absence of coughing, colic or other localising signs) is viral infection, and symptomatic treatment is all that is required. There are exceptions where fever can be associated with bacterial infection that warrants antibiotic treatment, so it is important for your vet to assess your horse if fever develops. But antibiotics are often not indicated, and prudent use is critical if we are to slow the rate of antimicrobial resistance. Wherever possible, localised management of a suspected infection is preferred. This may include regular cleaning and lavage of a wound, drainage and lavage of an abscess, or poulticing and drainage of hoof abscesses.

Extensive exposure

When we give a horse antimicrobials many different bacteria will be exposed to that antibiotic, from the natural bacteria that make up the gastrointestinal tract’s microbiota, to the natural bacteria on the skin, as well as any bacteria present within the wound. Additionally, the antibiotic may be excreted in the urine, causing environmental bacteria to also be affected. So, exposure to antimicrobials is far more extensive than the intended target: some of these bacteria will be susceptible to the antibiotic and will die, others may be inherently resistant, or of particular concern, some may develop resistance genes in a bid to stay alive. These genes can be spread to other bacteria and can also cause resistance to other antibiotics.

What are the impacts?

Antimicrobial resistance is developing at a frightening rate. This has led to dramatic increases in human deaths due to infection with bacteria that are multi-drug resistant and therefore in many cases untreatable. Just over one thousand Australians died in 2020, and worldwide it is estimated that close to 1.3 million people die annually, following infection with multi-drug resistant bacteria.

The golden era of antimicrobials and the dramatic increase in longevity associated with their discovery may well be coming to an end unless we act quickly and consistently to reduce the rate of antimicrobial resistance developing.

What needs to change?

Prioritising good management and infection control to help reduce the risk of infections is an important step in the fight against antimicrobial resistance. This may include: implementing biosecurity protocols on properties that house multiple horses, particularly in competition settings where horses leave the farm and are exposed to other horses; implementing vaccination programs to reduce the frequency of preventable conditions; and maintaining appropriate husbandry routines including dental examinations, farriery and appropriate parasite monitoring programs.

Ensuring good management, hygiene, and preventative health practices helps to reduce the frequency of ailments that might lead to antimicrobial prescribing. While most owners strive for and are achieving a high standard of care, it may be worth asking your vet if you have all bases covered, or whether you could make improvements in your horse’s preventative health program.

Duration of course

Another important step in the fight against antimicrobial resistance is to move away from set duration courses of antibiotics, and instead treat for the amount of time required to resolve infection and not longer. The outdated advice regarding dosing with antimicrobials for a set five or seven days needs to be forgotten. If it takes three days to resolve infection, the remaining days simply expose microbes to the antimicrobial unnecessarily, helping to drive antimicrobial resistance. Likewise, if you administer the antimicrobial for five days and the infection has not yet resolved, a discontinuation may enable the remaining bacteria to develop resistance. Antimicrobial treatment requires veterinary re-examination and assessment to confirm the appropriate duration of treatment needed to satisfactorily resolve the infection.

Due to the package size of antimicrobials in equine practice, it is not uncommon for owners to have antimicrobials remaining after the completion of a course. Understandably, they are often reluctant to throw them away as they are expensive and may be required in the future. However, it is critical that these medications are never used if they have not been prescribed by your vet. The decision to use antimicrobials is one that requires extensive consideration. The antimicrobial type, route of administration, dose rate, frequency and duration are all considered on an individual basis – and all are critical if antimicrobial stewardship is to help reduce the development of antimicrobial resistance.

Dr Sarah Gough, BVSc/BVet Bio (Hons 1), DipECEIM, EBVS, is a European and Australian Specialist in Equine Internal Medicine based at Apiam Hunter Equine Centre, Scone NSW.