The importance of an adjustable canter

To be successful in show jumping or cross country, you need to be able to adjust your horse’s canter speed and stride. CHARLIE BRISTER explains why.

In both show jumping and cross country, each course has a set optimum time that has been calculated by the course designer in relation to the length of the course. Obviously, the distance of a cross country course is going to be longer and the speeds are going to be faster, and it’s very important that riders train their horses at those canter speeds so that they develop a feeling for them, as well as getting their horses fit enough to have the appropriate canter for that level of competition and height of jump.

There’s a reason that in advanced eventing the canter speed is faster. You can’t go around a high level cross country course with the same canter speed that you would have in a 1.0m show jumping course. For example, to avoid time penalties, the speed required for a 5* cross country course is an average of 570 meters per minute over a distance of approximately 5.7 to 6.27 kilometres. The reason 570m/pm is an average speed is that there will be times when you’re going to have to collect the horse and be a lot slower (such as when you’re jumping a hollow combination, or a big drop fence), and then go faster than the average speed to make up for it.

What is by far the best is if you can make these transitions as smooth as possible for the horse, which quite often saves the most time. So, by having efficient transitions and a really responsive horse, you can make those changes in speed much more easily. [For more on downward and upward transitions, see Charlie’s article ‘Clear lines of communication’ in our September 2024 issue.]

When a horse is really strong in the bridle and dull to the leg, it takes a lot longer for you to make the change between being slower and then a bit faster, and that’s where you waste time. By improving those transitions and the communication between you and your horse, you’ll speed up your time without necessarily being faster, or by riding dangerously.

So how do you work out your canter speed? It can be very helpful if you’ve got a pre-training facility nearby, or somewhere that has a track where you have a really big area and you know the distances on the track. If you don’t have access to either of those facilities, but you do have a big paddock, get a trundle wheel and measure out a loop ideally of 570 metres. You can then practice riding this track at 570 meters a minute, and once you have an idea of what that speed feels like, practice speeding up and slowing down within the loop, but still finishing within your set time.

This is certainly going to be a lot easier if you have a friend timing you, or ideally, your eventing coach. An eventing coach can also help with your position and give you pointers on how to improve your horse’s transitions within the gallop and the canter. But it can be done on your own if you know the distance of the track, and use an app on your phone to time it.

In show jumping, the required speed is not as high. At the Olympic level, we’re looking at only 400 meters a minute, but I can guarantee you that when you’re riding a course of 1.6m show jumps at up to 400 meters a minute, things come up very, very quickly.

It’s a lot harder to have this canter speed without the horse getting too strung out. And that’s something to think about. Sometimes you need to lengthen the canter, but other times you need to increase the RPM, on a bigger horse for example, without the canter stride getting longer. This is often the case in show jumping, whereas on cross country we will want to lengthen the canter in a galloping part of the course.

In show jumping, the speed is faster at the higher levels because you need a bigger, stronger canter to jump those Grand Prix fences, while at the lower levels it’s a bit easier to get around at a slower canter. However, at home, most people train in a 60 by 20 metre arena, and work on getting their horses collected, listening and relaxed. Quite often they’re not training at competition speed, so when they get out to a competition and suddenly their horse is flying around with no brakes, their surprised reaction is ‘But they’re not like this at home’.

So it’s important that you ride in a big, strong competition speed canter at home. You have to adrenalise the canter a little bit to practice doing downward transitions from an adrenalised canter. Make sure you figure out what speed that canter is and how you’re going to measure it, so that you’re actually practicing the correct canter at home. You don’t want to be getting to the competition and then saying ‘Oh, my horse is too strong, I need a bigger bit’. That may need to happen at some point in a horse’s career, but it certainly should not be your first port of call.

Consistency of the canter is very important in show jumping. You will still want a slightly bigger or quicker canter for an oxer than for say, a vertical or a skinny triple bar, but by improving the consistency of your canter and making the transitions smoother, you’ll make it a lot easier for the horse to stay in balance and jump the fences. And if they listen, understand and respond to the aids as soon as they are applied, they’ll be able to focus on the fences rather than having to listen to you pulling and kicking all the time.

ESI International’s Dr Andrew McLean has analysed the number of rails horses had down in competitions in relation to the speed they’re travelling and the consistency of that speed. He discovered that the consistency of the canter at the correct pace leads to less rails down – another very good reason to work on your canter!

Within a course of jumps, whether show jumping or cross country, there are combinations on related lines and unrelated lines. You might have a combination of two or three fences, very rarely four (although at the high levels of eventing, you will sometimes see it). A combination is generally going to be either one or two canter strides between each fence. Three stride combinations are rare in show jumping but you’ll often see them in cross country. Generally, a related line would be anywhere from four to eight strides between the two fences, while an unrelated line is more than eight strides with some show jumpers going up to 10 strides, maybe even 11, but rarely more than that.

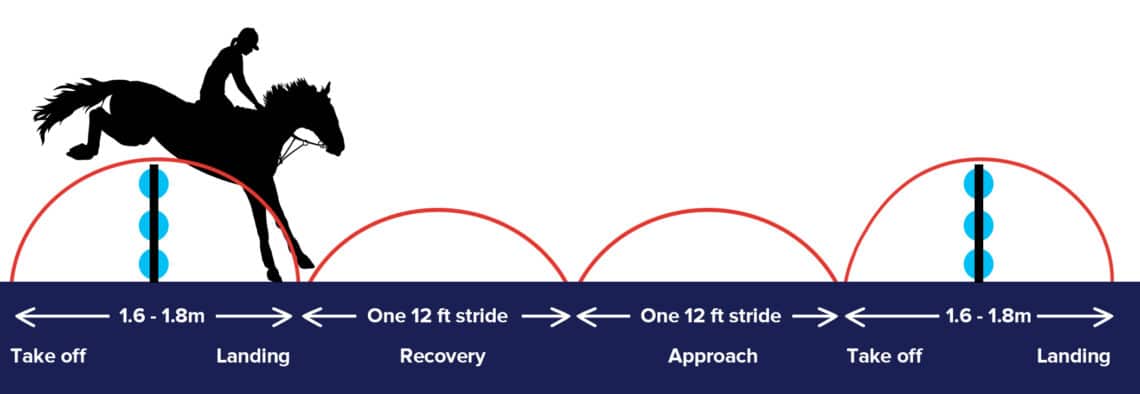

In show jumping, the course designer generally builds the course to a 12 foot canter stride. If there’s a one stride combination, they’re going to allow for the take off and landing at approximately 1.6 to 1.8 meters, and then a 12 foot canter stride before taking off again. So it’s important, especially for show jumping, that you practice riding in this 12 foot canter stride.

RPM, ground speed and stride length are all slightly different, but all very related. So if you walk a four stride related line, you’ll then know what canter you need to get four strides. If you have a small pony, you might do five strides, and that’s fine. But if you have a 16.2hh horse and you’re riding five strides in a four stride line, you’re probably underpowering the canter for a fence of that height, making it harder for the horse to clear the obstacle while probably collecting time penalties as well.

While adjustability and rideability exercises where you vary the number of strides between small fences, poles and cavalettis are very helpful in training, at a competition it’s very important that you try and get the correct number of strides. However, you might be on a 17hh Warmblood and jump in a bit too quickly over the first fence, and instead of pulling really hard on the horse’s mouth to get the correct number of strides, you land, keep going, and with one less stride in the six stride line the horse is going to be fine. But you can’t do that all the time, otherwise your horse will become a bit too fast and strung out.

In a cross country combination with related lines, course designers will quite often build the stride a little longer than 12 feet to account for the horse galloping and being a bit more strung out. But it’s important to note that when they do build a shorter stride, or a correct stride length, you have to pay a lot more attention. You’ll need to spend a little bit longer setting your horse up to have them balanced on the hind end so they won’t get too close to the front of the second obstacle, risking a rotational fall if they’re on the forehand, too strung out, and going too fast.

Charlie Brister of Brister Equestrian is an all-round horseman with expertise in retraining problem horses and coaching riders in all disciplines. You can follow him on Instagram.