Stringhalt – its symptoms, causes and treatment

Stringhalt is an involuntary flexion of one or both of a horse’s hind legs. Although it’s a rare disorder, it is nonetheless debilitating, as DR CIARAN MASTERS explains.

Stringhalt is a rare but peculiar and significant disorder that can affect the way your horse moves. Any horse can be affected by stringhalt and so an understanding of what it is and how it occurs is crucial to helping safeguard your horse’s wellbeing.

What is it?

Stringhalt, also known as equine reflex hypertonia, is a neuromuscular disease that causes an excessive upward flexion of one or both of the hind limbs when moving forwards. Characterised by a jerky flick of the leg, the onset can be sudden, or its appearance may be more progressive. The condition varies in severity and can be chronic or intermittent depending on the cause.

There are two main forms of the disease: the classic variety, and Australian stringhalt (sometimes referred to as pasture-related stringhalt), a form of stringhalt that occurs mainly in Australia, hence its name.

What are the symptoms?

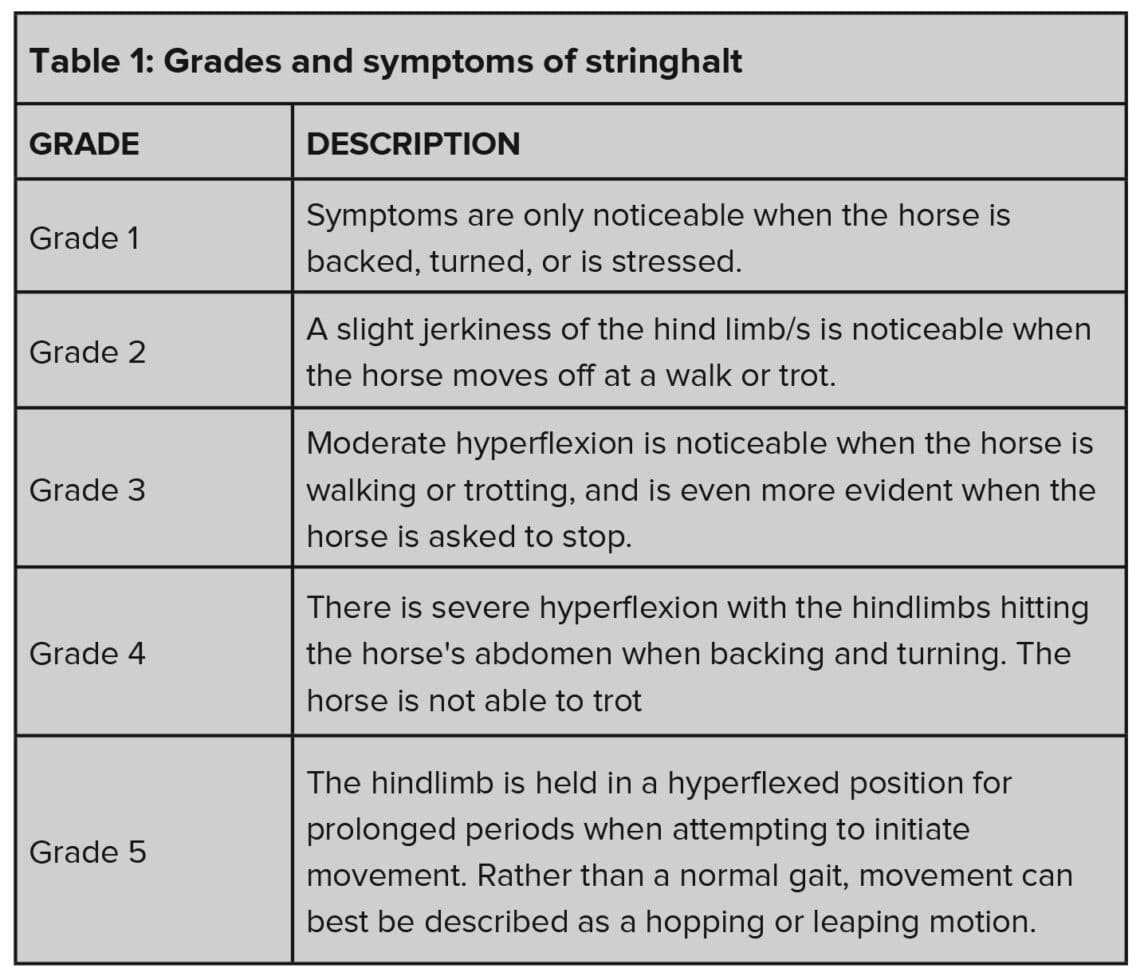

The most noticeable and characteristic symptom of stringhalt is the involuntary and exaggerated jerky flexion of the hind leg or legs. This can range from a subtle and spasmodic high step, to extremely jerky movements where the horse struggles to move without discomfort. A grading system has been devised to categorise the severity of the case (see Table 1).

Another common sign of stringhalt is an uneven gait that can almost look as if the horse is hopping. This can become more prevalent when the horse is asked to back up or turn sharply. Prolonged cases can also show signs of muscle wasting in the affected limb due to disuse and the altered gait.

Depending on the cause, and particularly with Australian stringhalt, horses may present with laryngeal paralysis and can be heard to be ‘roaring’. While this might initially seem to be a little bit strange, it occurs because similar to the hind legs (see below), the larynx is supplied by a long nerve and so can also be affected.

The horse may also have an upwardly fixed patella (stifle lock) and drag their hooves, and in severe cases, may not even be able to stand without assistance.

Unfortunately, many cases of stringhalt, especially classic stringhalt, are idiopathic, meaning the cause isn’t really known. We do know that it is a neuromuscular condition causing damage to the long nerves that supply the horse’s hind legs – although why this damage actually occurs is another unknown.

In some instances, the disease appears to originate from an injury. However, Australian stringhalt does seem to have a more specific cause. It is thought that Hypochaeris radicata, more commonly known as flatweed, cat’s ear or false dandelion, as well as certain other plants, including common dandelion and Mallow Weed, can cause a toxicity that sets off the condition. Due to this plant-induced toxicity, Australian stringhalt is often seasonal, usually occuring in summer or autumn.

What if my horse has stringhalt?

It may sound obvious, but should you suspect your horse is showing signs of stringhalt, the best next step is to call your vet. They can observe the horse and will maybe ask you to perform a set of manoeuvres with your horse that are designed to exaggerate any symptoms. A full clinical exam will also be carried out to check your horse’s neurological and general health status, and in some cases, an X-ray or ultrasound will be used to rule out injury. Your vet may also examine your paddock for signs of the offending plants.

How do we treat stringhalt?

Unfortunately, stringhalt is a complex disease and so does not have a single definitive treatment. In Australian stringhalt, the obvious approach is to remove the horse from the pasture if toxic plants have been found growing there. Once away from the toxins, the recovery time varies but on average is usually six to twelve months, although a full recovery may take up to two years. Unfortunately however, some horses may never recover.

Depending on the case and severity, phenytoin (an anti-seizure medication), anti-inflammatories and muscle relaxants can be administered under veterinary supervision. However, these offer only temporary relief. Physiotherapy and stretching can help improve muscle tone and coordination, which in turn can reduce the severity of the jerky movement, and vitamins B and E added to the feed have also been shown to have some therapeutic effect. In some idiopathic cases surgery may be required, although this is usually only resorted to in chronic cases where other treatments have been unsuccessful.

What’s the prognosis?

Stringhalt’s prognosis varies widely depending on several factors. With Australian stringhalt, once the horse is removed from the pasture the prognosis is usually good and most horses improve, even if they may take a considerable time to do so. Relapses can occur, but even severely afflicted animals can make a full recovery – and should a full recovery not be achieved, affected horses can still have a good quality of life.

Knowing what the culprit weeds look like will go a long way towards managing your horse’s pasture, and thus help prevent the onset of the disease. And remember, if you notice your horse has a little bit too much ‘spring’ in their step, be sure to call your vet – getting on top of stringhalt quickly will help to ensure the best outcome for your horse.

Dr Ciaran Masters BVetMed is an Equine Veterinarian currently working for APIAM Animal Health at Queensland’s Samford Valley Veterinary Hospital.