Thankfully it’s rare, but when it occurs your eagerly anticipated foal is in serious trouble. HEATHER IP recently went through this experience with a particularly precious baby.

A ‘red bag’ foaling – it’s something you don’t see often, but when you do it’s a serious emergency.

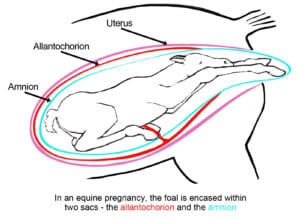

In an equine pregnancy, the foal is encased within two layers of sacs (see Diagram One). The outer sac is called the allantochorion, and the chorionic (outer) side of this sac attaches to the lining of the mare’s entire uterus. It is a deep red colour and has a texture like velvet, where millions of tiny velcro-like ‘fingers’ attach to the endometrium throughout the whole uterus, providing the foal with all the nutrients, oxygen and waste removal required throughout the pregnancy and birth.

Within the allantochorionic sac is allantoic fluid, and within that fluid is another fluid-filled sac, the amnion. The amnion is a translucent whitish membrane containing amnionic fluid and the foal itself. The umbilical cord passes from the foal, through the amnion to the allantochorion, allowing nutrient and waste transfer between the mare and the foal.

In a normal foaling, the waters break at the commencement of second stage labour, which means that the allantochorion ruptures at the level of the mare’s cervix, releasing the allantoic fluid (the ‘waters’) and allowing the foal to pass through the cervix encased in the inner membrane, the amnion. The first thing that is usually seen emerging from the mare’s vulva in a normal foaling is a whitish bubble containing amnionic fluid and the foal’s two front feet and nose.

If the appearance of the sac is more red than white, this is the chorionic side of the outer sac, indicating that the allantochorion hasn’t ruptured at the cervix and the placenta has separated from the endometrium too early. When this occurs, the foal no longer has an oxygen supply and every second counts. The foal needs to be delivered immediately to prevent it from being starved of oxygen, with likely fatal consequences.

Dreamy and Tilba

Early one morning in September, my five year old Warmblood mare, Dreamy, went into labour. I had been watching her from the caravan we have parked beside the foaling paddock, so as soon as she lay down for the first time, I went in to check on her. In a normal foaling it would be usual for the waters to break at around this point. In Dreamy’s case, she started straining, but the waters hadn’t yet broken. This was the first clue that this might be a red bag delivery. Sure enough, as she started to push, the red bag appeared. In Dreamy’s case, her waters did break at this point, but the fact that the red bag was visible was a sure sign that the foal was already being starved of oxygen. If her waters hadn’t broken naturally, I would have had to immediately cut open the allantochorion and deliver the foal as quickly as possible. It is worth noting that the allantochorion is quite a thick and strong membrane, so scissors or a scalpel blade should always be included in foaling kits.

In a red bag delivery, the longer the foal stays inside the mare, the longer it is oxygen deprived, so I knew that I had to act fast to get the foal out so it could breathe for itself. I grasped the foal by the front legs and pulled in a downward arc towards the mare’s hocks, but the foal was quite large and very, very stuck. After making very little progress, I called my long-suffering non-horsey husband out of bed and we both pulled until our hands and arms were burning.

A vet was called as soon as I realised I couldn’t get the foal out easily, but she was a 20 minute drive away and I knew that the foal would be dead by the time she arrived if we couldn’t get her out ourselves. After what felt like forever, with a little manipulation and a lot of cursing, we finally managed to get the foal out on the ground.

In a normal foaling, the first thing to emerge is a whitish bubble containing amnionic fluid, and the foal’s front feet and nose.

She appeared utterly lifeless on delivery. Normal foals start breathing as soon as the chest leaves the mare and usually sit up on their sternum almost immediately after foaling. This foal was not breathing and was completely unresponsive, as limp as a wet noodle, with blue gums indicating oxygen deprivation. I had a foal resuscitation pump in my foaling kit, which I am sure saved her life. After what felt like several minutes of desperate pumping, watching the faint pulse in her neck getting slower and slower, she finally took a breath on her own.

I couldn’t believe my eyes, as I was sure we were losing her. She lay flat and motionless for several minutes, taking noisy, laboured breaths. Then eventually she started to move and raised her head. It was at this point that the vet arrived. I am so thankful that I had the resuscitation kit and was able to resuscitate her myself, or I’m sure the outcome would have been worse.

For the next hour or so, the vet and I watched her gradually become brighter to the point where she eventually started trying to stand, but her legs were so weak and uncoordinated that even when being held up she couldn’t take weight on her legs. So we carried her onto an old horse rug and stretchered her into the horse float with Dreamy for a visit to the equine hospital.

A red sac indicates that the allantochorion hasn’t ruptured and the placenta has separated from the endometrium too early (Image by Julie Hewat, Rokewood Stud).

A foal that has been oxygen-deprived during birth will very often show signs of neonatal maladjustment syndrome, more frequently known as ‘dummy foal’. Our foal was showing every sign that this was the case, with an inability to stand and a lack of suck reflex. Dummy foals can make a full recovery, but only with very intensive nursing and veterinary care until they are able to live independently and nurse from the mare. Without this intensive care, they have a very poor prognosis as they are unable to feed themselves and obtain the vital colostrum.

Tilba lay flat and motionless for several minutes after resuscitation.

The filly, later named Tilba by her new owner, spent the next six days in intensive care, being nursed around the clock and being treated with oxygen, intravenous fluids and antibiotics. Dreamy was milked frequently and this was fed to the filly via a nasogastric feeding tube. As the days went on, Tilba gained strength and eventually started to nurse from Dreamy herself. After six days, we were so relieved to bring her home as a normal healthy foal.

Tilba and Dreamy in hospital, where Tilba was treated with oxygen, intravenous fluids and antibiotics.

Tilba is a Warmblood filly by international dressage winner Totilas. Her dam, Dreamy, is by De Niro, one of the most successful international dressage sires of all time. She has been named Cooramin Te Fiti, taken from the movie Moana. In the movie, Te Fiti is a beautiful island that has lost its heart and Moana is responsible for returning Te Fiti’s heart to resurrect its former magic, so the name felt right for this foal that had almost lost her heart.

Tilba’s arrival was an incredibly memorable and stressful one, but every day I am so thankful that we managed to pull her through, to grow up and have a chance at the dressage career she was bred for.

Heather Ip owns and runs Cooramin Sporthorsesin Wagga Wagga, where she breeds Warmbloods and performance ponies for dressage. For more information, visit cooramin.com.au

(All images courtesy Cooramin Sporthorses).